Australia and Papua New Guinea: A century of scientific partnership

Page last updated:10 December 2025

As Papua New Guinea celebrates 50 years of independence, it’s a great opportunity to look back at the much longer scientific story that we share with our northern neighbour. Since the early 20th century, Australian geoscientists worked alongside colleagues in Papua New Guinea to help understand and manage the impacts of the many geological hazards that occur in this part of the world.

Papua New Guinea is on one of the world’s most active and complex tectonic zones. The region is home to major earthquakes and frequent volcanic eruptions. Combined with flooding and landslides, this is a place where the power of the Earth is very clear—and Earth science is a vitally important way to understand and manage the impacts of that power.

Foundational information: surveying and mapping

In 1911 the first Australian geologist, Evan Stanley, was appointed to the Territory of Papua, and he made several journeys around the territory, publishing the first comprehensive geological maps of the area. Through dense jungle and deep river gorges, across jagged mountains and waterlogged swamps, the surveying teams used every resource available to produce accurate maps. And these were not only geographic maps: geological mapping, geophysical surveys, bathymetry, geochemical analyses and seismic observations all formed part of the growing picture of this beautiful part of the world.

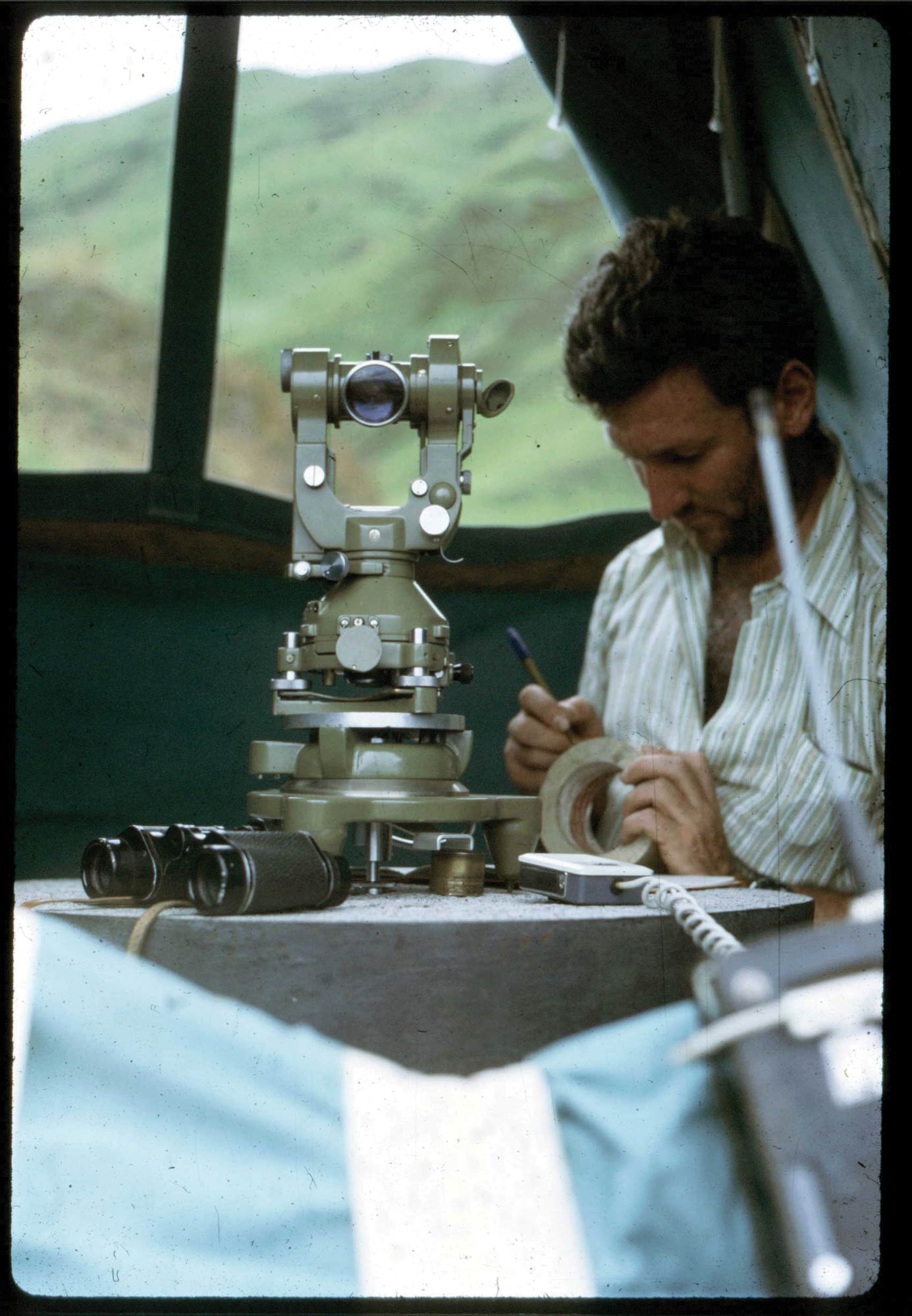

Early surveys were all done on foot, with parties of Australian and Papua New Guinean scientists making their way through difficult and complex terrain, and with little to no contact with the wider world. When aerial photography became common in the 1950s and 60s, it allowed scientists to finally get a large-scale view of the country, and it became fundamental to creating base maps and planning future surveys.

Australian Geologist D.E. Mackensie using air photograph mosaics to co-ordinate a new survey, 1969. Image: J. Zawartko

In the mid 1970s, with independence on the horizon, sixteen years of painstaking geological mapping was published as a series of 1:250,000 maps. The teams were determined that the soon-to-be independent nation of Papua New Guinea would have the best possible mapping data at their disposal.

And this data was of pivotal importance in helping to manage disaster risk. It created the foundational knowledge to understand the tectonic framework that underpins many of the natural hazards, such as earthquake, volcanic eruption and tsunami.

Earthquakes

Earthquakes are a routine part of life in Papua New Guinea, with at least 100 every year that are magnitude five or greater. These earthquakes can trigger landslides and tsunamis, destroy buildings and infrastructure, and cause ground shaking and liquefaction.

In this area, the Australian Plate is colliding with the west-moving Pacific and Caroline Plates. This interaction creates a complex and very active tectonic region, with many collision zones and active fault zones causing seismic activity.

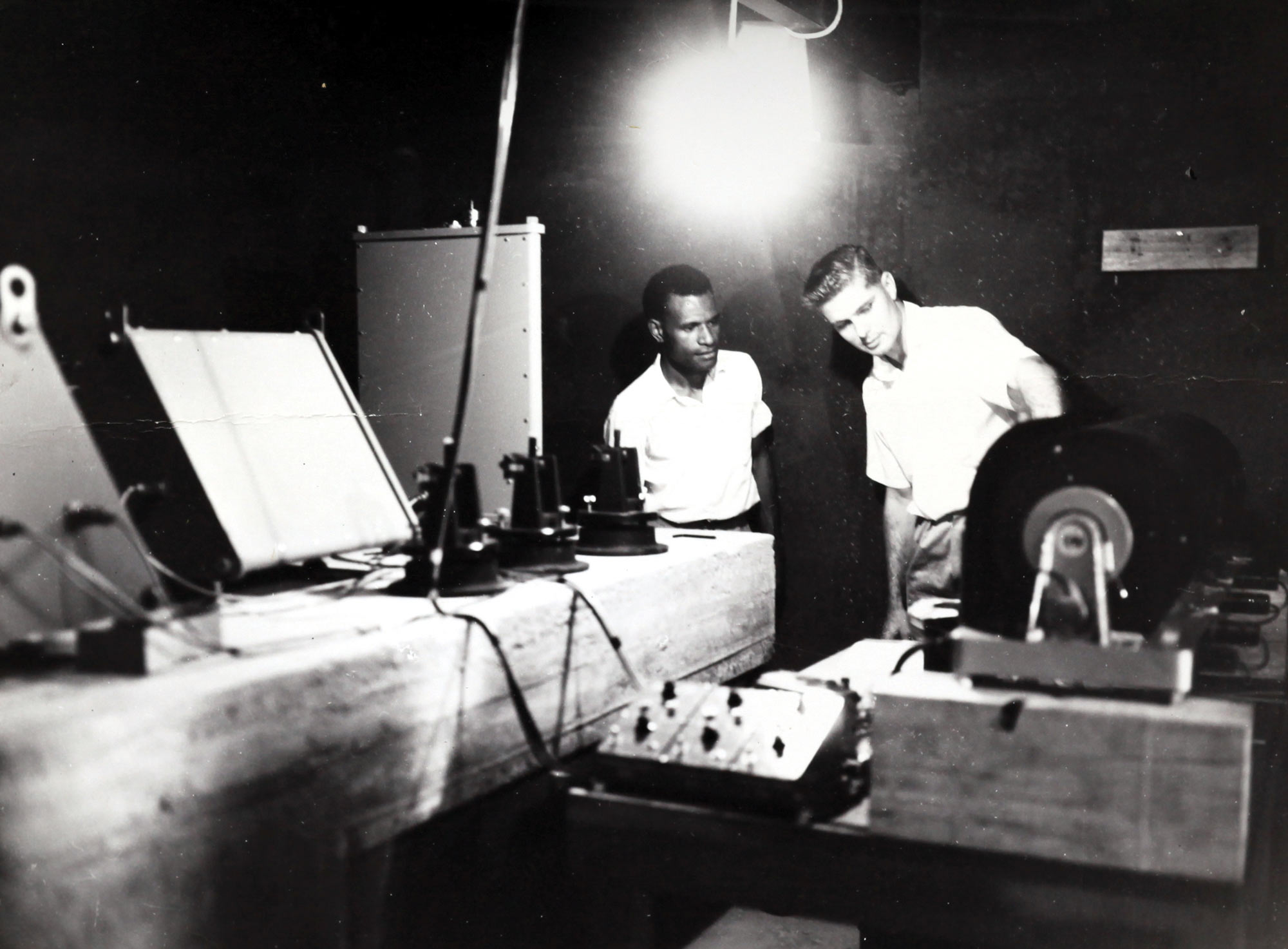

Port Moresby Geophysical Observatory was established in 1958 to make seismic, magnetic and ionospheric observations, connecting Papua to the Australian and global observation networks.

J. A. Brooks, leader of the Geophysical Observatory in Port Moresby, explains the workings of new seismological equipment to New Guinean technical assistant, Carson Noel, 1958. Image: UoW Archives

Seismic surveys and hazard mapping formed vital initial information on the areas where the risks were most concentrated. With a more detailed picture of the risks of earthquakes, to both people and infrastructure, real steps could be taken to manage the impacts.

While it is still not possible to predict the timing or size of an earthquake, by mapping areas of highest risk it is possible to focus the risk mitigation work on areas where it can have the best impact.

Decades of meticulous data collection came together to give a comprehensive seismic picture: using data and observations to form the understanding of the seismic risk.

Surveyor Steve Bennett records geodetic measurements during the 1973 Crustal Movement Survey of the Ramu Markham Fault. Image: J Steed

Community safety work is more than just science. The education of the community is very important, as is making sure communities are involved in the work that helps to keep them safe. The Community Based Seismic Network deploys modern low-cost seismometers in schools and community centres. In addition to monitoring seismic activity, this program performs an important education role, strengthening community awareness of natural hazards and how to keep safe if an event does occur.

The combination of decadal data with focussed scientific efforts made it possible to develop a comprehensive national seismic hazard assessment. This assessment, completed in 2019, showed that the earthquake hazard in Lae was particularly high. Crucially, it also gave an essential basis that was needed to start addressing this hazard and reduce the potential damage.

Australia worked with the Papua New Guinea government to update the building code and bridge design manual to reflect local seismic conditions and align with global best practice. In-country training was given to infrastructure design professionals and a range of professional development materials were developed, ensuring that the data, skills and knowledge necessary to manage this hazard stay in Papua New Guinea.

And this work is ongoing. Satellite imagery and lidar data continue to grow our understanding of the seismic history of the landscape, using information about past earthquakes to indicate how future earthquakes could look. Australian geoscientists work with local Papua New Guinean experts to conduct microzonation survey and identify areas where ground shaking could be amplified or dampened during an earthquake. Trenching activities show how previous large earthquakes have shaped the landscape, giving vital evidence of how future quakes might behave.

Leo Jonda (L) and Dan Clark (R) during trenching activities near Lae, 2025. Image: Geoscience Australia

Throughout all of this work, the cooperation and collaboration of scientists and experts from Australia and Papua New Guinea have been essential to delivering tangible results that can be implemented to help protect lives and livelihoods.

Volcanoes

Papua New Guinea has at least 14 active volcanoes and many more that are not currently active. The location of the country at the intersection of tectonic plates means that this is an ongoing and persistent hazard with the potential to cause significant damage and loss of life.

In 1937, twin volcanoes at Rabaul erupted, covering the town in destructive ash that collapsed buildings and killed at least 500 people. Following this eruption, authorities acknowledged the significance of instrumental monitoring and early warnings in mitigating the impacts of volcanic eruptions. An observatory at Rabaul was planned, and Rabaul Volcano Observatory (RVO) commenced operation in 1939.

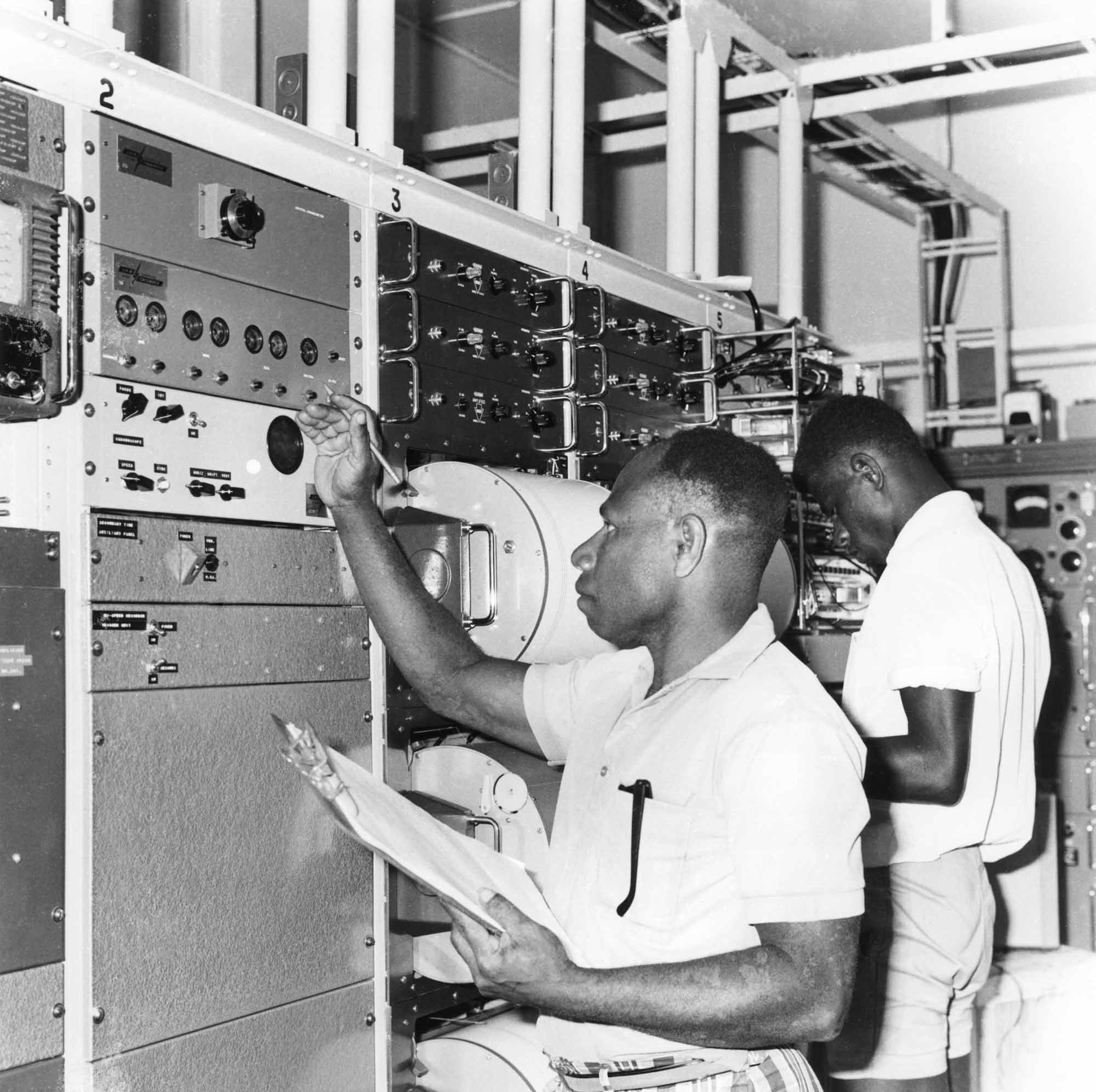

Ben Talai and Leslie Topue attend to monitoring equipment in the Rabaul Volcano Observatory recording room in the late 1960s. Image: Rabaul Volcano Observatory

Australian ‘Doc’ Fisher became the first full time volcanologist to be permanently based in the then-Territory of Papua. Experts agree that while accurately predicting volcanic eruptions is not possible, the more thoroughly monitored a volcano is, the more likely it is that some potential disaster can be avoided.

Doc Fisher can be seen here measuring the temperature of a fumarole (vent) at Rabaul in 1937. Image: Geoscience Australia

In 1951, a terrible tragedy struck when nearly 3000 people died in the hot clouds of volcanic rock, ash and superheated gases that erupted from Mt Lamington.

Australian volcanologist Tony Taylor and volcanological assistant Leslie Topue were called to the area after the eruption, and they helped to keep the relief and recovery crews safe with monitoring of the volcano. They made frequent trips to the eruption site and collected groundbreaking evidence about this type of explosive volcanic eruption, which continues to inform volcanological science.

Australian volcanologist Tony Taylor, volcanological assistant Leslie Topue, and patrol officer Bill Crellin ascending to the Mt Lamington crater, 1951. Image: Dr N H Fisher

This treacherous work was vital to the recovery effort. For their incredible work, Tony Taylor was later awarded the George Cross medal for his ‘conspicuous courage in the face of great danger’, and Leslie Topue was awarded the British Empire Medal ‘for courage and outstanding services in hazardous circumstances’.

In the 1960s observation networks were expanded to more volcanoes across Papua New Guinea. The RVO team designed innovative monitoring systems designed to work in the remote jungles and mountain tops of the country, feeding essential data to the scientists who work there every day. In the 1960s, Papua’s Ben Talai was the first local professional volcanologist, emblematic of the growing local scientific capability. Ben was later appointed leader of RVO in 1994.

Tony Taylor descends into the active crater at Langila volcano, 1952, measuring temperature and gas composition. Image: Max Reynolds

Australia and Papua New Guinea continue this vital work today, collaborating with local experts and institutions to improve monitoring, build local scientific expertise, and help communities become more resilient to volcanic hazards. And the Rabaul Volcano Observatory continues to be the centre of volcanic monitoring in Papua New Guinea: a wonderful legacy of scientific cooperation and achievement.

Keeping communities safe

Disaster Risk Reduction aims to prevent natural hazards (such as volcanoes or tsunamis) from becoming major incidents that significantly impact human life, infrastructure, the economy and the environment.

Geoscience Australian Senior Seismologist, Dr Hadi Ghasemi (centre) with Bialla International School staff after installing a seismic sensor in New Britain, Papua New Guinea in 2019. Image: Geoscience Australia

It integrates geological factors and scientific understanding of hazards, with social factors such as where people live and how prepared the community might be when these hazards occur.

Public awareness and education are a critical part of ensuring communities are prepared for natural hazards. The longstanding friendship between Papua New Guinea and Australia has significantly benefited both countries. Working together, step by step and side by side, we will continue to apply the best possible science to the challenges posed by natural hazards, and will do everything possible to keep people safe.

Dan Clark, Leo Jonda, Jonathan Griffin and Joseph Espi in Lae, working together to keep Papua New Guinea safe. Image: Geoscience Australia

Come and see!

The Earth science relationship between Australia and Papua New Guinea is being celebrated with a new photographic exhibition at Geoscience Australia’s headquarters in Canberra. The exhibition is open to the public during business hours Monday to Friday, excepting public holidays and the Christmas break.