News Ten years on: 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami

Page last updated:16 December 2014

The 2004 earthquake and tsunami

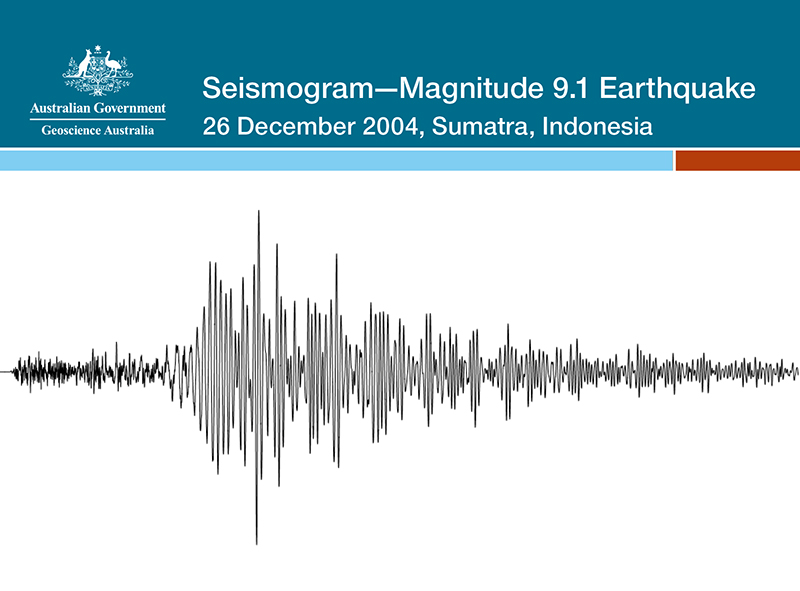

On the morning of 26 December 2004, a magnitude 9.1 undersea earthquake ruptured along a 1200 kilometre tectonic plate boundary off the west coast of Northern Sumatra and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

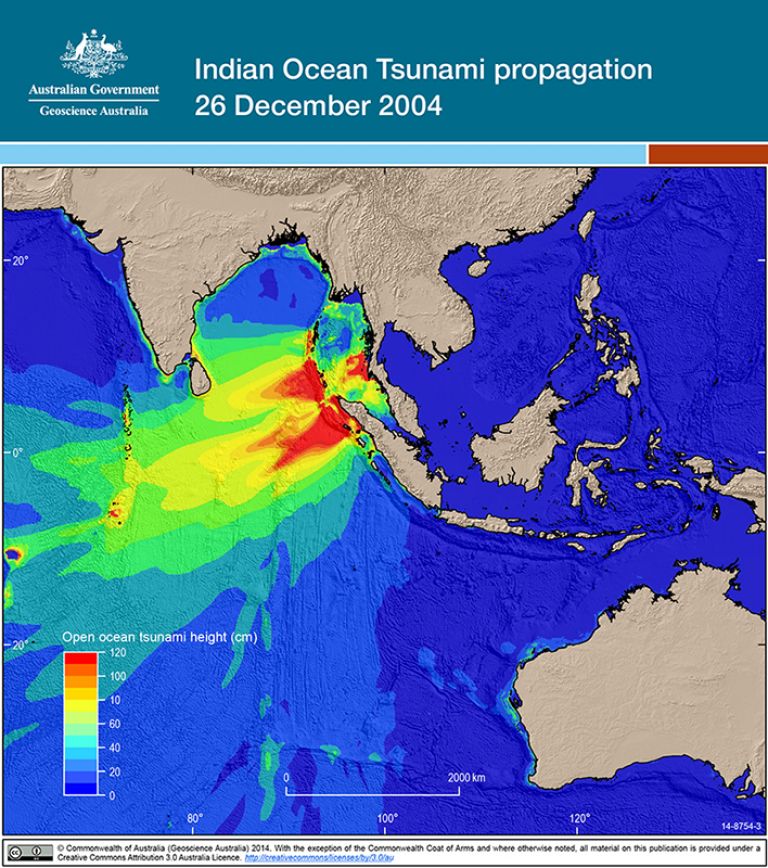

The earthquake generated a massive series of tsunami, devastating the immediate coastal areas of western Indonesia and spreading out across the Indian Ocean to impact communities in Australia, Burma, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Maldives, Seychelles, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Tanzania and Thailand. The earthquake is the largest event ever recorded in the Indian Ocean and is estimated to be the third largest recorded globally. It had enormous impact on Sumatra's infrastructure, housing and population, causing almost complete destruction prior to the arrival of the tsunami waves.

The earthquake is the largest event ever recorded in the Indian Ocean and is estimated to be the third largest recorded globally

Referred to as a mega-thrust, the earthquake began below the ocean floor in the subduction zone where the Indo-Australian tectonic plate meets the Sunda tectonic plate, pushing parts of Indonesia westward by 5-10 metres. The tsunami that followed recorded wave heights at over 30 metres in some areas of Indonesia.

The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake-tsunami event is the most devastating in recorded history and is estimated to have caused the deaths of between 220,000 and 300,000 people.

10 years after the Indian Ocean Tsunami: What have we learned?

Though no one realised it at the time, the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake was the first in a series of massive earthquakes to shake the globe. At magnitude 9.1 it is among the three largest earthquakes ever recorded since instrumental recordings began at the turn of the 20th century. The following seven years saw the occurrence of another three of the ten largest earthquakes ever recorded (including the giant earthquake and tsunami in northeast Japan in 2011).

The Australian tsunami warning system

While Australia's risk is considered lower, it is still vulnerable to tsunami threat from both the Pacific and Indian oceans, with waves able to arrive on our mainland in as little as two hours.

Australia was fortunate not to be in a direct path of the tsunami wave energy from the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, with most of the energy travelling west from Sumatra. However, a major earthquake south of Java could focus tsunami wave energies on the west coast of Australia. Similar threats exist for the east coast of Australia.

In response to the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and to mitigate against the risk of impact on Australia, the Australian Government pledged $68.8 million in the 2005-06 Budget to develop an Australian Tsunami Warning System (ATWS) over four years. The system would aim to:

- provide a comprehensive tsunami warning system for Australia

- support international efforts to establish an Indian Ocean-wide tsunami warning system, and

- contribute to the facilitation of tsunami warnings for the southwest Pacific region.

Over the following years, significant work was contributed to develop a warning system for Australia and the Indian Ocean region.

The establishment of the ATWS utilised existing scientific and technical expertise at Geoscience Australia, the Bureau of Meteorology, and Emergency Management Australia, as well as the diplomatic leadership of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

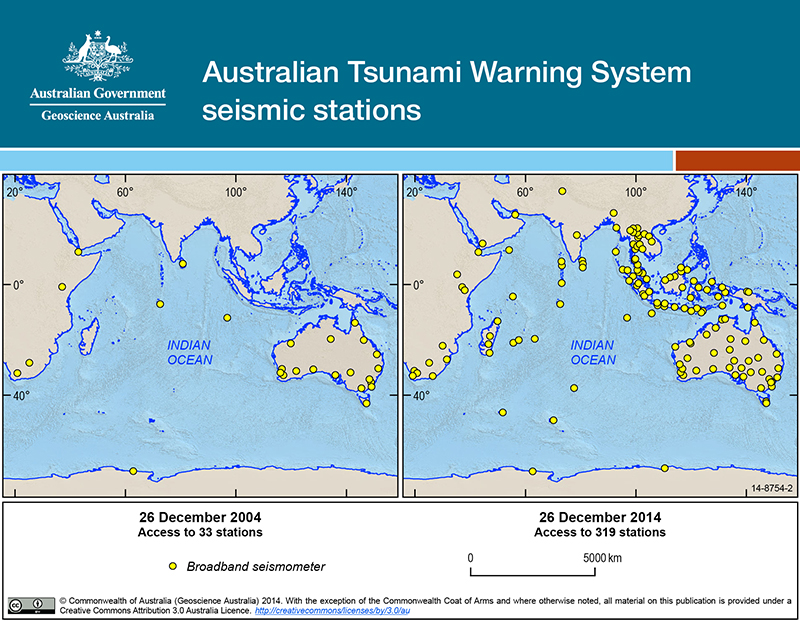

Geoscience Australia was provided funding to upgrade existing seismic stations - instruments used to record seismic activity across the globe, build new seismic stations (both within Australia and overseas), and to access real-time digital seismic data from new and existing international seismic networks. The organisation also established a 24/7 operation centre.

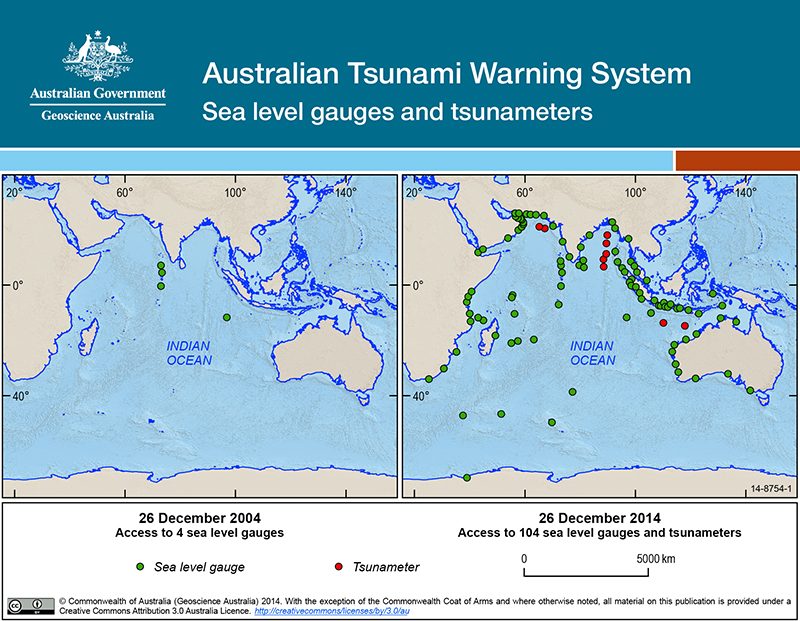

Bureau of Meteorology was funded to upgrade existing tide gauge sea level stations - instruments used to measure surface wave height and variation, build new tide gauge stations within Australia and overseas, and to install new tsunameter buoys - instruments designed specifically to monitor energy variance in deep water - located in deep ocean locations near subduction zones. The Bureau built on its existing 24/7 operations and infrastructure to develop a tsunami forecasting and warning capability.

Emergency Management Australia (within the Attorney General's Department) was funded to develop a general community understanding of the tsunami threat to Australia and to develop and present a program of tsunami awareness and preparation for emergency managers, industry and the general community.

In October 2008, the designated Joint Australian Tsunami Warning Centre (JATWC) - 24/7 monitoring and warning operation centres in Canberra and Melbourne - were officially opened and fully operational. The JATWC is Australia's authority on earthquake and tsunami monitoring and warnings, with the infrastructure to provide accurate and timely advice for Australia and its offshore territories.

In response to the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and to mitigate against the risk of impact on Australia, the Australian Government pledged to develop an Australian Tsunami Warning System

Where we are now

Australia's world-class tsunami warning system now operates 24 hours a day and is a major component of a multinational Indian Ocean tsunami warning system.

At the time of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, Australia relied on the existing Australian Tsunami Alert System, which provided a limited notification and alerting capability to emergency services and relevant authorities.

There were no mitigation and response strategies in place at the community level; Geoscience Australia had 33 seismic stations (developed for domestic earthquake monitoring and alert services); and the Bureau of Meteorology had 26 sea level monitoring stations, but with very limited capability to access the information in real-time. There was no tsunami forecasting capability.

Now, Australia has a comprehensive tsunami warning system for the nation including its offshore territories, and supports the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System (IOTWS).

Within 10 minutes the Joint Australian Tsunami Warning Centre (JATWC) can now detect and notify of an earthquake with the potential to generate a tsunami. Within a further 2-5 minutes, the JATWC can forecast tsunami threat and potential impacts, providing the public, media, emergency managers and other relevant authorities with tsunami warnings.

Geoscience Australia now have access to over 300 seismic stations across the world, enabling comprehensive analysis, and Bureau of Meteorology now operate 44 coastal sea level stations and 6 deep-ocean tsunameter buoys, monitoring sea level in real-time in the Indian and Pacific oceans. The Bureau of Meteorology also have access to more than 100 coastal sea level stations and 46 tsunameter buoys operated by other countries in our region.

In October 2011, Australia, along with India and Indonesia, became one of three countries providing real-time, rapid-response tsunami information to countries bordering the Indian Ocean. This advice supports these countries in issuing timely and confident warnings to their affected coastal communities.

In April 2013, an interim seismic and sea level monitoring system ceased and the Indian Ocean region had an independent tsunami warning capability. The IOTWS is made up of contributions from Member States of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO around the Indian Ocean - mainly Australia, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Thailand. Significant contributions were also made by the United States, Japan and Germany.

Australia has a comprehensive tsunami warning system for the nation including its offshore territories, and supports the Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning System