Opal

Last updated:10 November 2022

Introduction

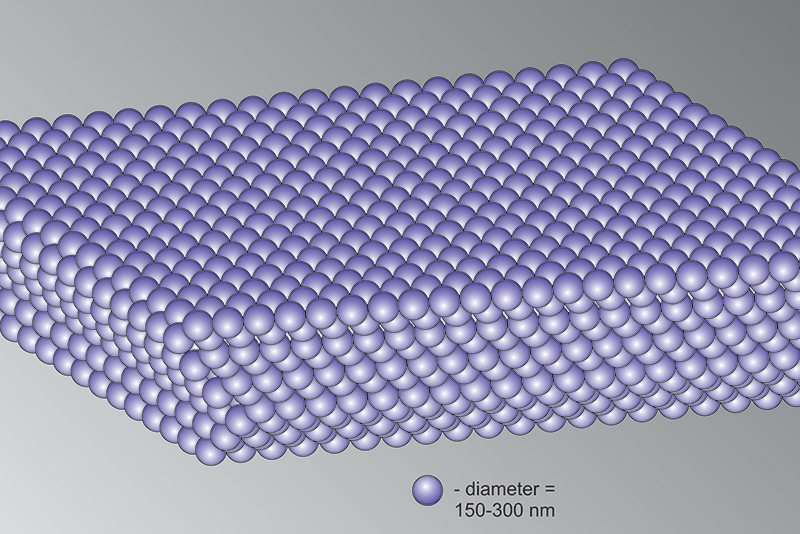

Does someone in your family own a ring or pendant that contains an opal? An opal is a 'gemstone' - that is, a mineral valued for its beauty. Gemstones are most often used in jewellery and examples include diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires, jade, opals and amethysts. Gems generally get their colour because of certain metals contained in the mineral (for example purple amethyst is quartz containing tiny amounts of iron). However opals are unique because they display a rainbow-like display due to their intrinsic microstructure which diffracts white light into all the colours of the spectrum.

Properties

Opals are multi-coloured and consist of small spheres of silica arranged in a regular pattern, with water between the spheres. The spheres diffract white light, breaking it up into the colours of the spectrum. This process is called 'opalescence'. Larger spheres provide all colours, smaller ones only blues and greens. Opals that have a predominantly red colour are very rare as they only occur where larger silica spheres were deposited.

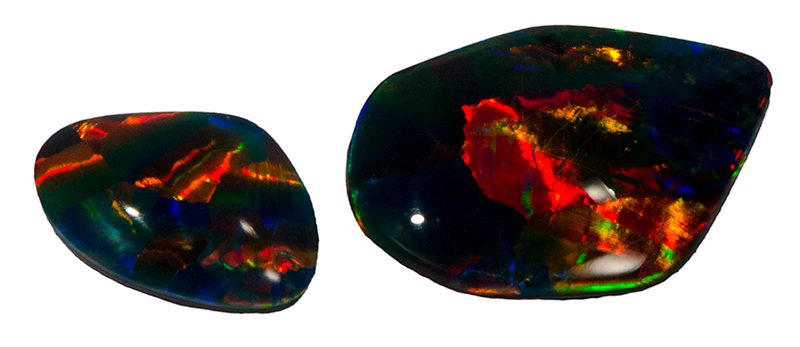

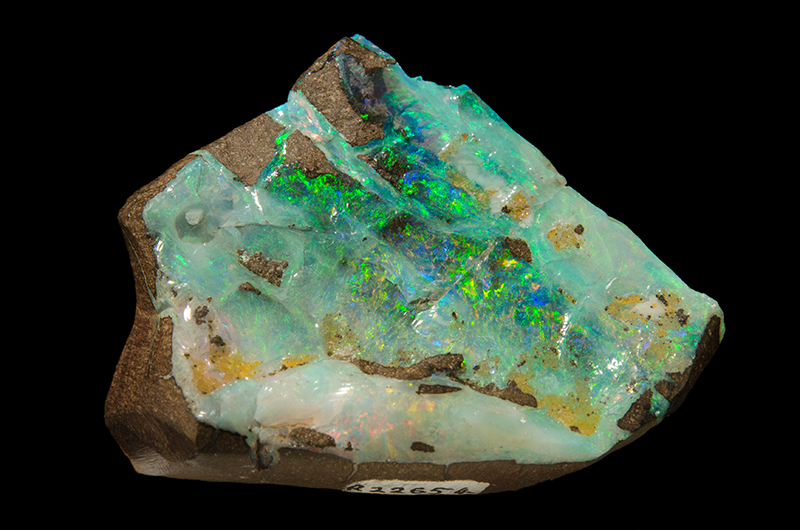

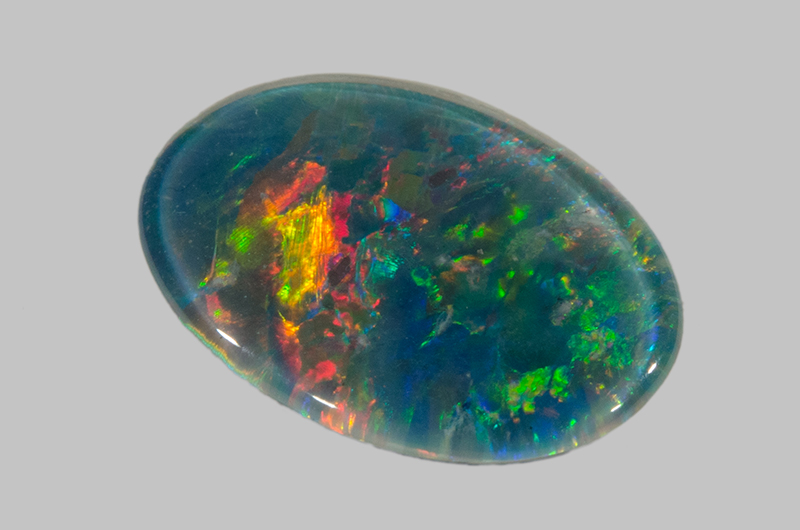

White opals have delicate, pale colours on a lighter background. Black opals (very rare and valuable) have a dark background and colours ranging from brilliant red through to greens, blues and purples. Boulder opals are cut with the natural host rock, ironstone, on the back.

The Properties of Opal

| Chemical Symbol | SiO2nH2O |

|---|---|

| Name | There is some uncertainty around the origin of the word opal - it may come from the Greek opallos meaning 'to see a change (of colour)' or may be Sanskrit for '(precious) stone'. |

| Ore | Opal ore |

| Relative density | 2.09 g/cm3 |

| Hardness | 5.5-6 on Mohs Scale |

Uses

Opals are used in jewellery and ornaments.

History

Opal artefacts several thousands of years old have been discovered in East Africa. As early as 250 BC the Romans prized opals, thought to have come from mines in Eastern Europe, the ancient world's main source of opals. There are many aboriginal dreamtime stories that feature opal.

Australian opals discovered during the late 1800's found little favour with European markets but their commercial value increased in the 1900's and in 1932 Australia took over as the major producer of opals in the world and remains the largest producer to this day.

In 1915 a group of people were prospecting for gold at the edge of the Great Victoria Desert northwest of Adelaide. Making camp one night, a 14 year old boy found an opal. This started an 'opal rush' and soon the settlement of the Stuart Range Opal Field was founded, better known now as Coober Pedy and together with Lightning Ridge in NSW, the bulk of the world's opal continues to be produced.

Formation

In Australia, precious opal is found in Cretaceous age sandstones and mudstones. These sedimentary rocks were deeply weathered and this weathering released silica into the groundwater. Small faults and joints in the rocks formed pathways for movement of the groundwater as it penetrated downwards.

Impermeable barriers between the sandstone and the underlying rocks trapped the silica-carrying groundwater where it slowly hardened into a gel forming opal in veins and lenses.

Opals are frequently layered and if a rare red layer is present it is at the base in the thinnest portion of the vein and indicates that gravity played a part in the arrangement of the silica spheres.

Australia is the only part of the world where opalised animal and plant fossils have been found. At Lightning Ridge in NSW, small opalised dinosaurs and primitive early mammalian remains, together with shallow marine shellfish and crustaceans have been found. Probably the most famous opalised fossil is Eric the Pliosaur (Cretaceous age marine vertebrate) which was found at Coober Pedy and now forms part of the Australian Museum collection. Not only is the opalised skeleton of this animal preserved, but also the stomach contents of its last fish meal are replaced with opal. Opalised fish bones and shelly mollusks are also fairly common at Coober Pedy, SA and are valued according to the appearance of the individual specimen and the intensity of the play of colours.

Spectacular mineral replacement with opal can also occur. The so called ‘opal pineapples’ found at White Cliffs, NSW are opal pseudomorphs of the mineral ikaite. Queensland opal deposits occur in non-marine sedimentary rocks and opalised animal remains are very rare, however fossil wood fragments showing annual growth rings and cellular wood textures occur and sometimes these are beautifully replaced with precious opal.

Resources

Opal is found around the world (Brazil, Mexico, Honduras and the western US) however Australia produces 95% of the world's precious opal and it is our official national gemstone. See Google Arts and Culture - Australian opals or Australian National Gemstone for further information.

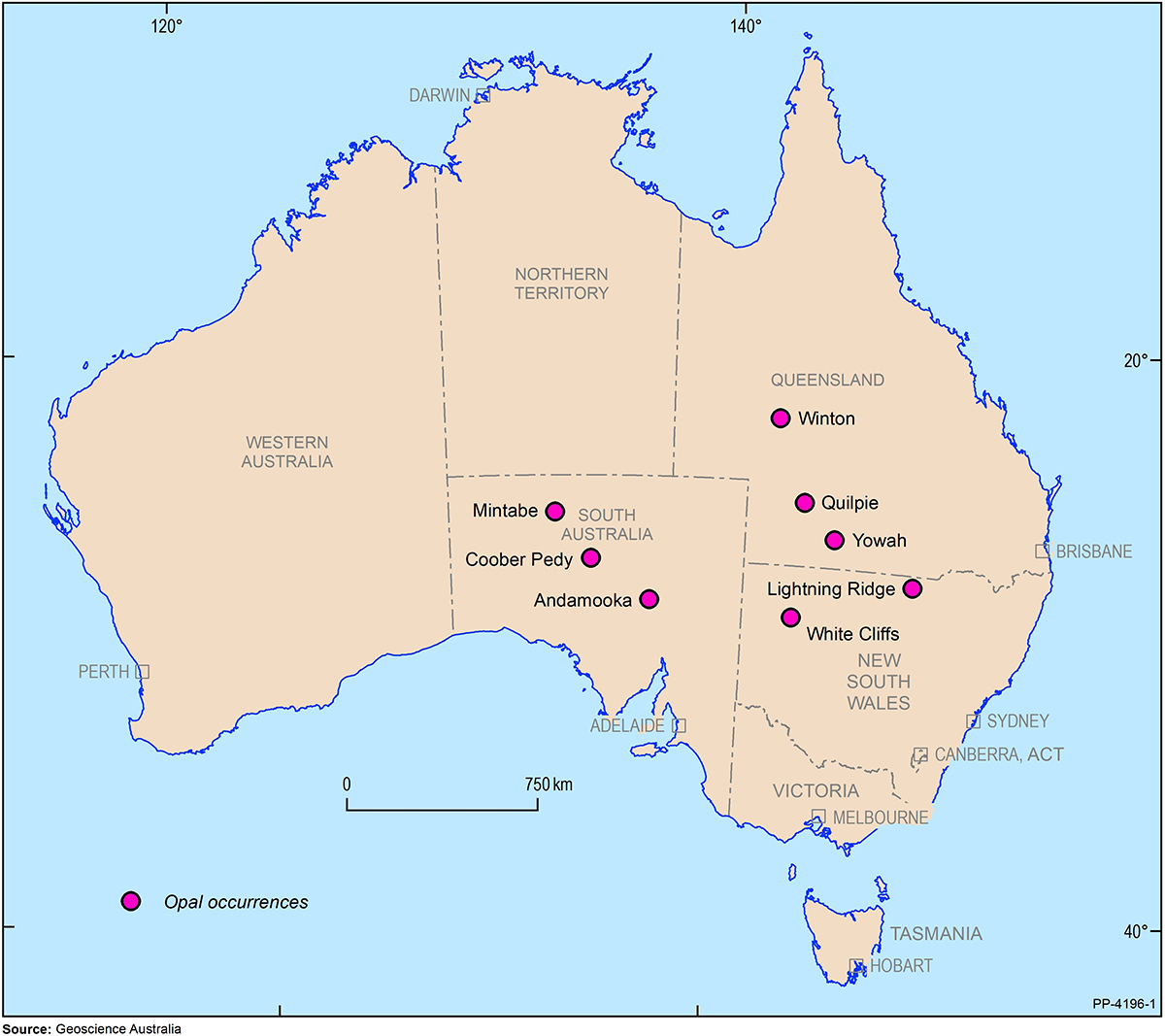

Opal was first mined commercially at Listowel Downs in Queensland in 1875 and later at White Cliffs in NSW. Today, Coober Pedy (SA) is the main producer of white opal, though in recent years this field has expanded and all types of opals are found. Other centres in SA include Andamooka and Mintabe. Lightning Ridge (NSW) is renowned for black opal and formerly White Cliffs was a large producer of high quality opal. Boulder opals (opals in concretionary ironstone) are mined in Queensland from numerous localities in a zone extending from the Eulo and Cunnamulla district in the south and northwest for a distance of over 700 km to Kynuna in the north. The towns of Quilpie, Yowah and Winton are the main opal mining and wholesale centres.

Opal deposits are found in very old weathered profiles developed in sedimentary rocks of late Oligocene and early Miocene age. These profiles are for the most part concealed below surficial sand and soil cover and it is comparatively rare that outcrops containing precious opals occur. As a consequence, the remaining in situ opal resource is considered by geologists to be very large. However, future development will increasingly rely on sophisticated geological and geophysical exploration methods.

Mining

Historically opal was mined most commonly by two or more individuals by shaft sinking and tunneling and following the opal ‘level’ using picks and shovels. A hand operated winch was used to haul buckets of excavated material to the surface. Today this industry is highly mechanized but is still in the hands of individuals who work within small mining leases or claims which are operated according to different state mining regulations. For example, except under special circumstances, only underground mining is allowed in NSW, whereas in South Australia both underground and open cut mining are permissible. In Queensland open cut mining is the norm and bulldozers and 20 to 40 tonne excavators are widely used.

Exploration is undertaken by surface prospecting and drilling. The use of 9-inch auger drills is the favourite choice for opal miners, as these drills are capable of recovering fairly large samples of the opalised zones. Many of these rigs are equipped with wet (puddlers) or dry (rumblers) rotating screens to separate harder drill chips which may include opal from the enclosing softer sediments. Because precious opal occurs in well-defined stratigraphic and structural traps, geophysical surveys using magnetic, resistivity, shallow seismic and ground penetrating radar have been used with varying success. Recently it was discovered that the ‘opal level‘ and opals themselves are slightly radioactive and gamma ray logging of drill holes can provide evidence for the presence of precious opal, even if the drill hole was a ‘near-miss’ and failed to bring opal fragments to the surface.

Mining is undertaken by drilling approximately 1 metre diameter vertical shafts using large diameter bucket drills. By these means a bulk sample of about one cubic metre or more is brought to the surface and is examined, usually by washing and sieving, to extract opal fragments. If potentially economic opal is found, then drives or tunnels are dug using jack hammers or underground hydraulic excavators. The excavated material is either sucked to the surface using ‘blowers’ or by automated bucket winches or conveyors. At Lightning Ridge all the excavated material is trucked to large processing centres known as puddling dams, where modified concrete trucks rotate, wash and screen the ore for several hours, until only the harder fragments remain. Once the washing is completed, the hard material is hand-sorted and any precious opal removed for assessment, cutting, polishing and eventual sale. Most of the opal in the concentrate is of the non-precious variety or ‘potch’ mixed with a much smaller amount of potential gemstone. From the processing of a complete truck load of material (typically 5 to 10 cubic metres), even from a very good mine, the rough precious opal recovered in most instances would easily fit into a shoe box.

'Noodling' is when people search through old mullock heaps for pieces of opal that might have been missed in the initial mining operation. For health and safety reasons it is illegal for visitors to enter mine mining leases or claims without specific permission of the owners. However state governments have set aside former opal mining areas and a fossicking licence is usually all that is required to carry out hand mining and noodling.

Processing

Once mined, opal ore is either hand sorted or mechanically washed and screened to separate the hard material, which is then visually assessed and separated according to size and colour. Queensland boulder opal, occurs as veins or centre fillings in small to large, nodular accumulations of ironstone composed of hematite and goethite. These boulders are sorted by hand as mined material is slowly tipped from the excavator bucket and those that have opal indications are taken to a rock saw where they are sliced to expose opalised veins. Most opal boulders contain empty spaces or are filled with non-precious opal or “potch” and are worthless. Some contain a mixture of potch and precious opal. On rare occasions a group of boulders may contain only precious opal and are very valuable ‘bonanza’ grade opal occurrences. Those slices which contain precious opal are graded according to size and colour and are ‘blocked out’ into rectangular or cubic shaped pieces, prior to specialist cutting and polishing of the final gemstones.

Because opal frequently occurs as thin seams of material within a host or matrix rock, some deposits are cracked or are so thin and fragile that they are not suitable for stand-alone jewellery. Very thin irregularly shaped or twisted veins, matrix opal and blebs of opal in silicified rock are frequently carved into figurines, paper weights or ashtrays. Large slices of opal rock are made into very expensive, wall panels, tiles and coffee tables.

Opal gemstones are marketed in several ways and reputable jewelers provide information as to the manufacturing process in which individual opals are constructed. Most of the labor intensive work and value adding is carried out overseas.

- Solid Gemstones. Opals shaped and domed into a cabochon showing a brilliant array of colours are the most precious. Stones that have a strong play of red together with splendent luster of orange, blue and green hues are the rarest and hence the most valuable and are sold according to their carat weight. Many solid opals are cut to irregular shapes in order to preserve as much as possible of the original opal and the majority of Queensland boulder opals are cut in this manner. As a consequence, each individual opal requires a specially designed setting, enclosed with gold, platinum or silver and the setting may be enhanced with other precious stones.

- Opal Triplets. These are thin slivers of precious opal about 0.5mm thick which are sandwiched between a backing made of black plastic, industrial glass or black (potch) opal and a transparent domed top, made from glass or clear quartz. The best triplets have black potch opal as the backing and clear quartz for the top. These layers are glued together using a suitable epoxy resin and the life of the opal is only as good as the glue that binds the layers together. The transparent cover magnifies the opal colour pattern and the black backing reflects the light through the assembly giving enhanced brilliance to the opal. These opals are commonly seen in Australian jewelry stores, particularly at airports and are sold at a fraction of the cost of solid opal gemstones. Most triplets are constructed to specific calibrated sizes so they can be fitted into mass produced, necklace, pendant or earring settings.

- Opal Doublets. A slightly thicker opal slice, usually greater than 2mm, is glued to a black base and then shaped and polished to a cabochon style. These are less commonly seen in the market and are more expensive than opal triplets.

- Matrix opals. These are solid opals which incorporate a varying amount of non-opal material such as opalised ironstone (Queensland matrix) or opalised silicified quartzite (Andamooka matrix). In some instances matrix opals are dyed to darken the enclosing rock which has the result of enhancing the play of colours.

- Opal carvings and specimens. Some opals that have inclusions of non-opal rock fragments are carved by highly skilled craftsmen into informal shapes or into shapes of familiar animals, such as fish, reptiles or birds. These objects often command high prices that are based on the intricacy of the individual carving and the colour intensity of the precious opal used.

- Opal beads. These are relatively rare as it is difficult to find opal material of sufficient quantity and of uniform hardness for perfect spheres to be made in a beading machine. Some Queensland and Andamooka opal matrix have been successfully used to make beads of exceptional beauty.

- Watch faces. Good quality watch faces are made from a single very thin slice of precious opal. Lesser quality faces are made from opal chips that are glued together and then sliced to form a composite face.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Dr Brian Senior for scientific review.