Australia's Energy Commodity Resources 2025 Geothermal

Page last updated:23 October 2025

Geothermal

| Production capacity | |

|

Electricity – | |

|

Direct use 107.4 MWth* ( 13% since 2020) |

|

Exploration 124 tenements# ( 12%) |

|

Status Early stages of development |

Notes

MWth = Megawatts thermal; *direct use production capacity as of January 2023; #exploration tenements as of December 2024 include 28 granted and 96 under application areas, up from a total of 111 in 2023.

Highlights

- Australia’s largest geothermal system began operating at the Australian War Memorial in October 2024. The innovative closed loop system relies on 32 km of vertical boreholes, drilled as deep as 150 m, fitted with over 130 km of pipework to form an underground heat exchanger. This provides both heating and cooling via high efficiency chillers and heat pumps.

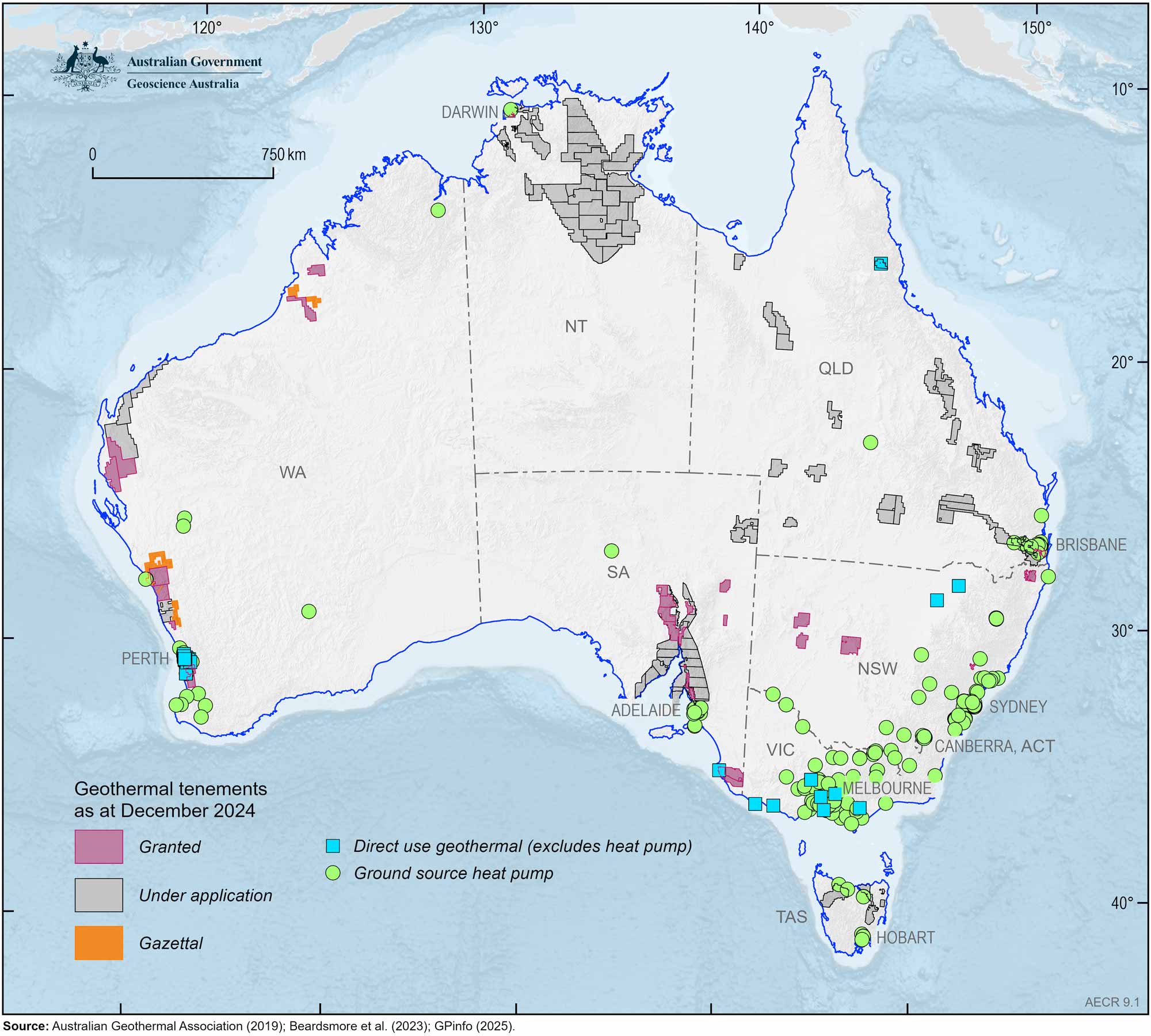

- The development of geothermal energy for utility-scale electricity generation remains limited to small-scale trial projects in Australia but has recently experienced a resurgence of interest as evidenced by a significant increase in permit applications across the country (Figure 9.1).

- Recent international breakthroughs in geothermal technology have the potential to significantly impact on the future development of geothermal energy in Australia. These include improved efficiency in power generation technology (which reduces the minimum temperature required), breakthroughs in Enhanced Geothermal System technology and the rapidly developing sector of Advanced Geothermal Systems, which utilise closed loop technology that eliminates the need for permeable reservoirs.

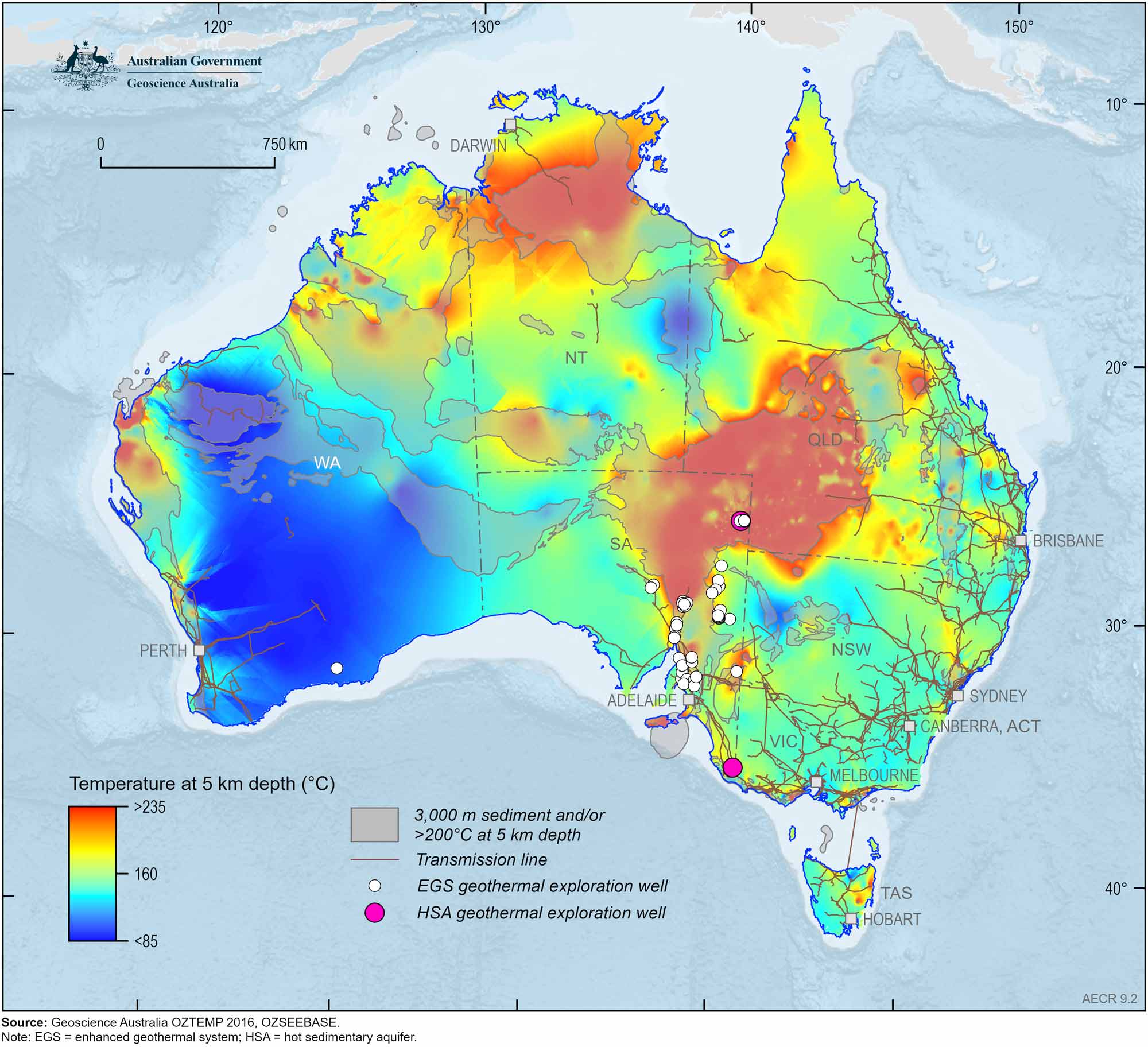

Australia’s geothermal resources

Globally, most geothermal electricity generation is located in regions where active volcanism creates high heat flows due to the presence of shallow magma. Australia has no known active volcanism and generally has lower geothermal gradients compared to many countries. In Australia, temperatures of >160°C are not reached until depths of 3 km across most of the country (Figure 9.2). Consequently, Australia’s geothermal resources are considered to be unconventional and are classified as either an enhanced geothermal system (EGS) or a hot sedimentary aquifer (HSA). The heat source for Australia’s unconventional resources is a combination of radiogenic heat production from rocks in the upper crust and conducted heat from the mantle.

Figure 9.2. Predicted temperature at 5 km depth, showing geothermal exploration wells and regions with >3 km sediment depth and/or predicted temperature of >200°C at 5 km (Gerner and Holgate, 2010).

In addition to electricity generation, technologies also exist to use geothermal heat for industrial and heating processes—such as drying and cooling and for spa baths/hot springs—these are collectively called direct-use applications. Also, at depths of several metres beneath the land surface, the temperature is quite stable year-round, and ground source heat pumps (GSHP) can be to used to heat and cool buildings.

Box 8.1 Conventional and unconventional geothermal systems

Geothermal energy resources can be classified into conventional and unconventional systems. Conventional geothermal systems are characterised by thermal, permeability and fluid properties that are favourable to the heat resource being extracted by drilling only. Conventional geothermal resources usually occur at depths <3 km. Unconventional geothermal systems have sufficient heat but lack the permeability and/or fluid for to achieve sustained fluid flow and therefore require stimulation to extract heat. Unconventional geothermal systems occur over a range of depths, up to 7 km.

Hot sedimentary aquifer (HSA) resources

Hot sedimentary aquifers (HSA) are shallow (less than 3 km) and usually have good natural permeability, provided that the sediments have not undergone metamorphism. The HSA resource in Australia could be substantial, as sedimentary basins with effective aquifers cover most of the Australian continent. However, only a few basins are known to have high enough geothermal gradients for higher-temperature HSA applications such as electricity generation. These include the Otway Basin (South Australia, Victoria), the Gippsland Basin (Victoria), the Perth Basin (Western Australia), the northern and southern Carnarvon basins (Western Australia) and the Great Artesian Basin (GAB; Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory).

Deep, high-temperature HSA resources have been tested in two locations: in the Otway Basin in 2010 (Panax Geothermal Pty Ltd’s Salamander 1 well); and in the Cooper Basin in 2011 (Geodynamics Pty Ltd’s Celsius 1 well). Both wells measured high temperatures, but neither achieved sufficient water flow rates (Budd and Gerner, 2015). The risk of unsuccessful wells could be reduced through improved 3D seismic mapping, resource modelling and implementing a play fairway mapping approach to identify areas where optimal aquifer/reservoir quality are likely to occur (South Australia Centre for Geothermal Energy Research, 2014). It can be concluded that deep HSA reservoirs have not been adequately tested in Australia.

Enhanced geothermal system (EGS) resources

Data compilations of predicted temperature at 5 km depth suggest that there are substantial areas on the Australian continent where temperatures exceed 200°C at this depth. This is considered the required temperature for geothermal electricity generation to be technically feasible. Australia therefore has the potential to contain world-class unconventional geothermal energy resources (Budd et al., 2008).

Deep, high-temperature EGS resources have been tested and hydraulically stimulated in two locations in Australia at depths greater than 4000 m. In the Cooper Basin, Geodynamics Pty Ltd developed the Habanero project in 2012; and east of the Flinders Ranges, Petratherm Pty Ltd drilled Paralana 2 in 2009. The Paralana project was not completed, as sufficient funds were unavailable for the drilling a second well into the fractured reservoir. It can be concluded that deep EGS reservoirs are yet to be adequately tested in Australia. However, significant technical developments overseas with EGS suggests that the technology may yet hold significant potential for Australia.

A potential alternative to EGS for electricity generation is Advanced Geothermal Systems (AGS). AGS is different to EGS in that they are closed loop systems that do not involve fluids penetrating the rock from one well to another. The technology works similarly to a GSHP except under hotter conditions and involving significantly longer wellbores (Department of Energy, 2024). Perhaps the most notable closed loop geothermal project is the Eavor Technologies demonstration project in Germany. The project involves four loops drilled to approximately 4–5 km depth and is estimated to produce 8 MW of power in 2027.

Geoexchange and other heat exchange resources

In geoexchange systems (also known as Ground Source Heat Pumps), the Earth acts as a heat source or a heat sink, exploiting the temperature difference between the subsurface and atmosphere. The temperature of the Earth just a few metres below the surface is much more consistent than atmospheric temperature, particularly in seasonal climates. These resources do not require the addition of geothermal heat and are perhaps better described as improving energy efficiency (up to 50% in comparison with the commonly used air-sourced heat pumps).

To utilise these stable subsurface temperatures, water or another fluid is pumped through pipes into the ground to change the temperature of the circulating fluid. Examples of systems in use are the Sydney Opera House (using Sydney Harbour as a water-loop heat exchanger), Sandown Village in Tasmania (using stored effluent as a heat exchanger) and most recently the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The facility at the Australian War Memorial is the largest geothermal system in Australia and began operating in October 2024. The innovative closed loop system relies on 32 km of vertical boreholes, drilled as deep as 150 m, fitted with over 130 km of pipework to form an underground heat exchanger to provide with a combined 7,850 kW of both heating and cooling via high efficiency chillers and heat pumps.

Australian Capacity

Electricity generation

No Australian geothermal electricity generation facilities were active in 2024. Four small projects have been trialled over the last two decades, the most recent being a small-scale (310 kW) HSA Organic Rankine Cycle geothermal power station in Winton, Queensland, in 2019 (ThinkGeoEnergy, 2019). Earlier small scale applications include the Mulka Station facility that produced 0.02 MW of electricity the late 1980s (Burns et al., 2000), the Habanero (Innamincka Deeps) Project 1 MW pilot plant, which generated from an EGS resource for five months in 2013 (Geodynamics, 2014), and Ergon Energy’s low temperature geothermal power station at Birdsville, which sourced hot (98°C) waters at relatively shallow depths from the Great Artesian Basin between 1992 and 2017 (ThinkGeoEnergy, 2018).

There continues to be interest in geothermal electricity generation in Australia. Greenvale Energy Limited in collaboration with CeraPhi Energy are assessing the potential for geothermal power generation at Greenvale’s Longreach tenement in Queensland (ThinkGeoEnergy, 2023). Within Energy has increased its geothermal portfolio with the addition of three new tenements in Queensland (ThinkGeoEnergy, 2022). Whitebark Energy has also acquired tenements in Queensland and is exploring opportunities for hydrogen production via electrolysis (Whitebark Energy, 2024). In Western Australia, Strike Energy is advancing a HSA geothermal prospect with an inferred resource of over 200 MWe (mid-case) located 300 km north of Perth, within the Permian Kingia Sandstone, where temperatures in excess of 160 °C have been identified at depths of ~4000 m (Strike Energy, 2022; Ballesteros et al., 2020).

Direct-use technologies

According to Beardsmore et al. (2023), recent years have seen steady growth in terms of direct use geothermal in Australia, both with and without heat pumps. Large-scale direct-use HSA systems, such as those used to heat swimming pools or provide hydronic heating systems and commercial-scale geoexchange systems, are increasing in number in Australia (Figure 9.1).

Established and effective examples of direct-use geothermal systems include Robarra (Robe, South Australia) and Mainstream Aquaculture (Werribee, Victoria), both growing barramundi using 28–29°C bore water. Midfield Meats (Warrnambool, Victoria), uses warm bore water (boosted to 82°C) for washing and sterilising its industrial meat processing facility. The use of geoexchange technology at scale in housing developments and other large commercial applications has become increasingly common. Prominent examples include the Geoscience Australia building in Canberra and the 72 MWth (megawatts thermal) Barangaroo water-loop heat rejection cooling system. In October 2024, Australia’s largest GSHP project began operations at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra (ThinkGeoEnergy, 2024).

As of January 2023, over 36 MWt of installed capacity for direct use of geothermal heat from hot aquifers has been identified (Beardsmore et al., 2023), an increase of 3 MWt (9%) since 2020. Ground source heat pump capacity is estimated to be 71 MWt, an increase of 9 MWt (14.5%) since 2020.

International production and consumption

The world’s installed geothermal electricity generation capacity has been growing over the past decade, estimated at approximately 16.2 GW in 2023 (Table 9.1; IGA, 2024). In 2023, global geothermal power plants produced approximately 96-98 TWh of electricity which was about 0.3% of the world’s electricity generation (IGA, 2024; IEA, 2024). Geographically, 72% of installed generation capacity resides along tectonic plate boundaries or ‘hot spot’ features of the Pacific Rim (World Energy Council, 2016). All of these are igneous convective resources. In contrast, only 20% of total installed generation capacity resides in convection fields situated along spreading centres and convergent margins within the Atlantic Basin. A disproportionate percentage of installed generation capacity globally resides in island nations or regions (43%). Virtually all these resources occupy positions either at the junction of tectonic plates (such as Iceland) or within a ‘hot spot’ (e.g. Hawaii; World Energy Council, 2016). Technological improvements have made it possible for most countries to use shallow low-temperature geothermal resources in addition to higher-temperature resources, and these opportunities are expanding rapidly.

Australia is significantly lagging behind the leading geothermal electricity–generating countries (Table 9.1), with no installed capacity. Similarly, Australia’s use of geothermal energy is insignificant when compared to that of the world leader, China (Table 9.2). In 2023, Australia was ranked 43rd in the world in direct-use geothermal utilisation (International Geothermal Association, 2024).

Table 9.1 Installed geothermal electricity generation capacity and generation for the top ten countries, Australia, and global total in 2023

| Rank | Country | Installed Capacity 2023 MWe | Generation 2023 GWh |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 3,889 | 18,702 |

| 2 | Indonesia | 2,335 | 16,592 |

| 3 | Philippines | 1,952 | 11,670 |

| 4 | Turkey | 1,717 | 10,840 |

| 5 | New Zealand | 1,055 | 7,820 |

| 6 | Mexico | 1,002 | 4,511 |

| 7 | Kenya | 952 | 5,590 |

| 8 | Italy | 916 | 5,917 |

| 9 | Iceland | 755 | 5,788 |

| 10 | Japan | 546 | 2,661 |

| 27 | Australia | 0.3 | 0 |

| Global total | 16,211 | 96,556 |

Abbreviations

MWe = megawatts electrical; GWh = gigawatt hours

Notes

Source: International Geothermal Association (IGA), 2024

Table 9.2 Selected world direct-use geothermal installed capacity and utilisation, 2023.

| Rank | Country | Installed capacity | Energy consumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| (MWth) | (TJ/year) | ||

| 1 | China | 100,220 | 828,882 |

| 2 | United States | 20,713 | 152,810 |

| 3 | Sweden | 7,280 | 67,680 |

| 4 | Germany | 5,381 | 32,184 |

| 5 | Turkey | 5,113 | 85,000 |

| 43 | Australia | 107 | 1,164 |

| Global total | 173,303 | 1,476,312 |

Abbreviations

MWth = megawatts thermal; TJ = terajoules.

Notes

Source: International Geothermal Association (IGA), 2024

References

Australian Geothermal Association, 2019. Census of Geothermal Projects.

Australian Renewable Energy Agency, 2014. Looking Forward: Barriers, Risks and Rewards of the Australian Geothermal Sector to 2020 and 2030. Commonwealth of Australia.

Ballesteros, M, Pujol, M., Aymard, D. and Marshall, R., 2020. Hot sedimentary aquifer geothermal resource potential of the Early Permian Kingia Sandstone, North Perth Basin, Western Australia. Geothermal Resources Council Transactions, 44, 477–503.

Beardsmore, G., Ballesteros, M., Davidson, C., Larking, A., Pujol, M., 2023. Australia – Country Update, Proceedings, World Geothermal Congress 2023, Beijing, China (October 8-13, 2023)

Budd A. R. and Gerner, E. J. 2015. Externalities are the dominant cause of faltering in Australian geothermal energy development. In: Proceedings of the World Geothermal Congress, Melbourne, 19–25 April 2015 (last accessed July 2025).

Budd, A. R., Holgate, F. L., Gerner, E., Ayling, B. F. and Barnicoat, A., 2008. Pre-competitive geoscience for geothermal exploration and development in Australia: Geoscience Australia’s Onshore Energy Security Program and the Geothermal Energy Project. In: Proceedings of the Sir Mark Oliphant International Frontiers of Science Australian Geothermal Energy Conference, Gurgenci, H. and Budd, A.R. (eds), Record 2008/18, Geoscience Australia, Canberra,1–8.

Burns, K. L., Weber, C., Perry, J. and Harrington, H. J., 2000. Status of the geothermal industry in Australia. In: Proceedings of the World Geothermal Congress 2000, Kyushu–Tokohu, Japan, 28 May –10 June 2000, 99–108.

Department of Energy, USA, 2024. Pathways to Commercial Liftoff: Next-Generation Geothermal Power.

Geodynamics Pty Ltd, 2014. Habanero Geothermal Project Field Development Plan, 9 October 2014.

International Energy Agency (IEA), 2024. The Future of Geothermal Energy.

International Geothermal Association (IGA), 2024. Geothermal Energy Database, 2023 data.

International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). 2025. Energy Transition Technology: Geothermal Energy (last accessed July 2025).

Gerner, E. J. and Holgate, F. L., 2010. OZTemp - Interpreted Temperature at 5km Depth Image

Lund, J. W., Toth, A. N., 2021. Direct Utilization of Geothermal Energy 2020 Worldwide Review, Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2020+1, Reykjavik, Iceland, April - October 2021

South Australia Centre for Geothermal Energy Research, 2014. Program 2 Summary Report, ARENA Measure: Reservoir quality in sedimentary geothermal resources.

Strike Energy Limited, 2022. Mid-West Geothermal Power Project Inferred Resource Statement, announcement to the Australian Securities Exchange 5 May 2022.

ThinkGeoEnergy, 2018. Birdsville in Australia abandons plans for renewal of geothermal plant (last accessed July 2025).

ThinkGeoEnergy, 2019. 310 kW Winton geothermal power plant in Queensland, Australia starts operation (last accessed July 2025).

ThinkGeoEnergy, 2022. Within Energy acquires new geothermal exploration permits in Queenslands, Australia (last accessed July 2025).

ThinkGeoEnergy, 2023. CeraPhi and Greenvale complete geothermal study in Longreach, Australia (last accessed July 2025).

ThinkGeoEnergy, 2024. Australian War Memorial switches on geothermal heating and cooling system (last accessed July 2025).

Whitebark Energy, 2024. Whitebark Energy instigates near term Hydrogen Commercialisation Pathway study. ASX Release 16 May 2024.

World Energy Council. 2016. World Energy Resource, Geothermal 2016.

Data download

Data tables and full report are downloadable from the Geoscience Australia website.