Australia's Energy Commodity Resources 2025 Overview

Page last updated:24 October 2025

Welcome to the fifth edition of Geoscience Australia’s assessment of Australia’s Energy Commodity Resources (AECR 2025). AECR 2025 provides resource estimates of the nation’s non-renewable energy commodity resources as well as an overview of projects and policy developments related to clean energy technologies. Non-renewable energy commodity resource estimates include oil, gas, coal, uranium and thorium as at the end of 2023. Estimates are grouped according to commodity type, reserves and annual production. Clean energy technologies are rapidly being developed in Australia to meet emission reduction targets. These technologies include carbon capture and storage (CCS), zero and low emissions hydrogen production, as well as geothermal energy resources.

Australia’s Energy Commodity Resources

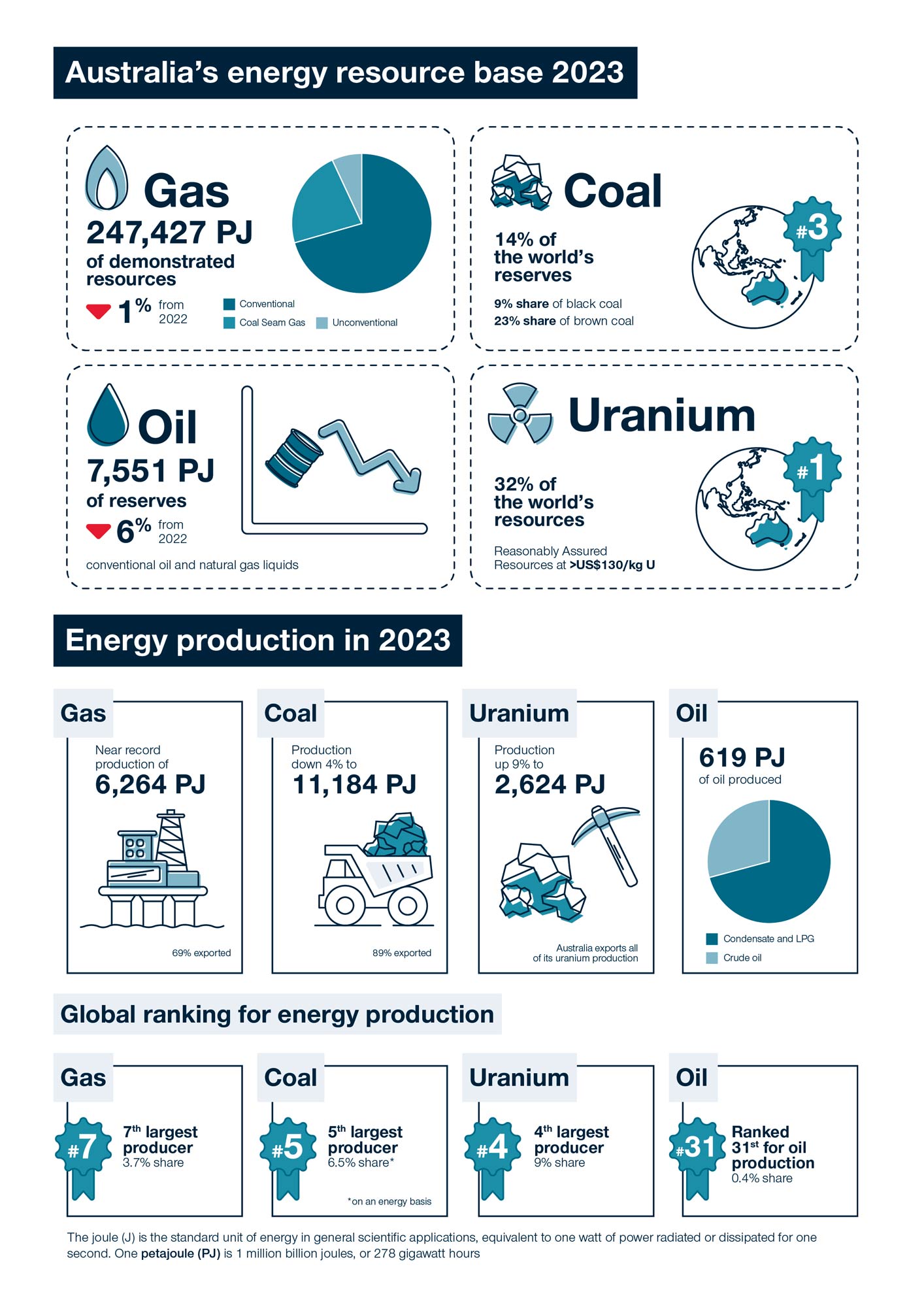

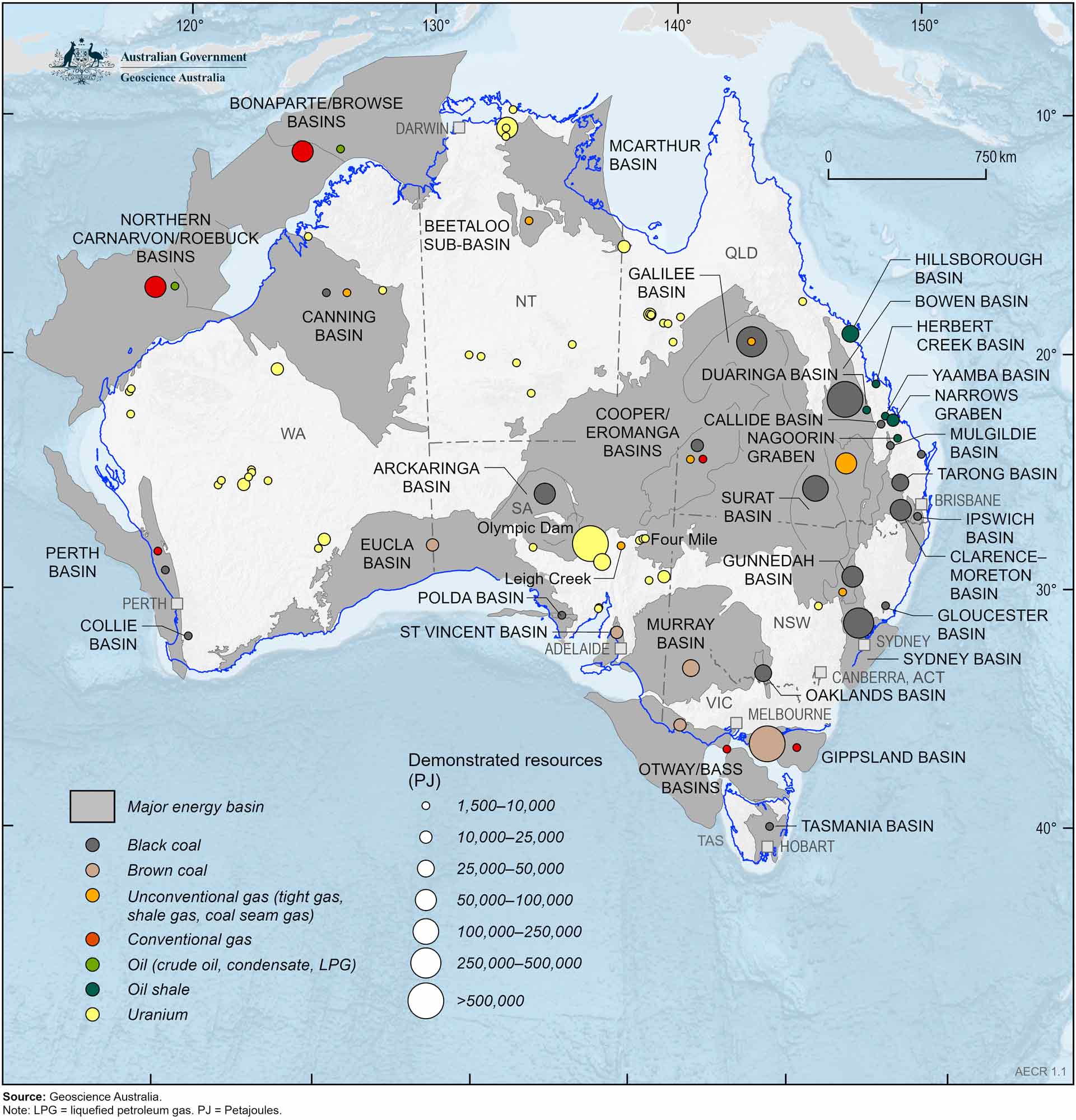

Throughout 2023, Australia continued to be a key global net energy exporter with a strong and diverse mix of energy resources across the continent, contributing 9% of uranium, 7% of coal and 4% of gas to global energy production (Figure 1.1).

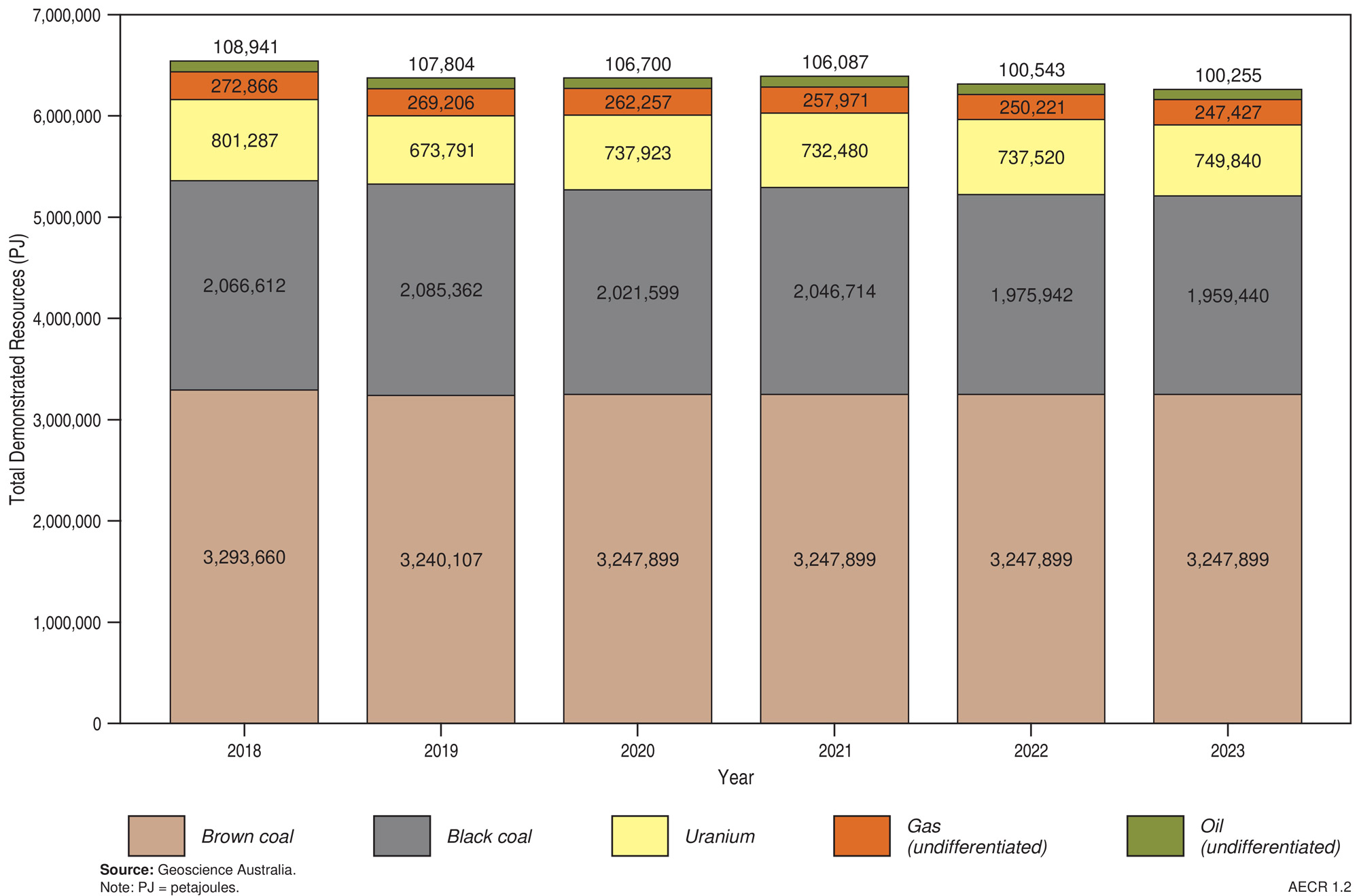

In 2023, Australia’s total demonstrated energy commodity resources were 6,304,862 petajoules (PJ; Table 1.1), down just 6,894 PJ (0.1%) from 2022. The small overall decline is largely attributable to a 16,502 PJ (0.8%) decrease in black coal total demonstrated resources (TDR) and a 2,085 PJ (1.2%) decrease in conventional gas TDR, offset by a 12,320 PJ (1.7%) increase in uranium TDR. In 2023, with the exception of unconventional oil resources, the TDR of each of Australia’s non–renewable energy resources remained within 5% of the previous year’s estimates (Table 1.1).

Since 2021, Geoscience Australia has published annual reports on Australia's energy commodity resources, enabling a medium-term overview of trends in Australia’s energy resource base (see Figure 1.2). Relative to 2018, in 2023 there has been a 4% (238,504 PJ) decline in Australia’s total non–renewable energy resources. Observations for individual resources since 2018 include:

- An 8% decrease in total oil resources (including shale oil), with a 30% decline in crude oil resources as many offshore fields near end of life and cease production, and a 167% increase in Australia’s emerging unconventional oil resources.

- An overall decline in gas resources of 9%, including a 10% decline in conventional gas resources, a 12% decline in coal seam gas resources and a 7% increase in unconventional gas resources.

- Total demonstrated resources of black coal and brown coal have decreased by 5% (107,172 PJ) and 1.4% (45,761 PJ), respectively. These reductions are greater than what can be attributed to production alone.

- A 6% decline in uranium resources, though Australia still accounts for approximately one-third of the world’s known resources.

In 2022-23, after 3 years of contraction, Australia’s total energy consumption grew by 2% (DCCEEW, 2024a), in line with the 2% increase in global primary energy demand in 2023 (Energy Institute, 2024). However, in 2023 Australia’s total production of energy commodities decreased by nearly 3%, with declines in production observed for most resource types (Table 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Distribution of Australia’s major non-renewable energy resources in 2023 (by basin or deposit), which contain total demonstrated resources greater than 1,500 PJ

Table 1.1 Australia's total demonstrated non-renewable energy resources, reserves, production and estimated reserves life in 2023

| Resource | Unit | Note | TDR 2023 | TDR % change 2022–2023 | Producing basins /deposits | Production 2023 | Production % change 2022–2023 | Reserves 2023 | Reserves % change 2022–2023 | Reserve Life 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude oil | PJ | 1, 2 | 4,555 | -4.9 | 10 | 182 | -21.7 | 1,346 | -8.8% | 7 |

| Condensate | PJ | 1, 2 | 14,534 | -1.7 | 11 | 397 | -2.1 | 5,786 | -3.3% | 15 |

| LPG | PJ | 1, 2 | 1,307 | 1.0 | 6 | 40 | -18.7 | 419 | -28.8% | 10 |

| Oil shale | PJ | 1 | 78,966 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | - | - |

| Unconventional oil (undifferentiated) | PJ | 1 | 893 | 6.2 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | - | - |

| Conventional gas | PJ | 1, 2 | 174,625 | -1.2 | 11 | 4,671 | -2.7 | 74,586 | -4.5% | 16 |

| Coal seam gas | PJ | 1, 2 | 55,867 | -0.9 | 4 | 1,593 | 2.0 | 30,562 | -1.0% | 19 |

| Coal seam gasification | PJ | 1, | 2,622 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | - | 1,153 | 0.0% | - |

| Unconventional gas (undifferentiated) | PJ | 1 | 14,313 | -1.6 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | - | - |

| Black coal | PJ | 2, 3, 4 | 1,959,440 | -0.8 | 95 | 10,784 | -3.9 | 1,855,256 | -0.9% | >100 |

| Brown coal | PJ | 2, 3, 4 | 3,247,899 | 0.0 | 3 | 401 | -3.6 | 730,660 | 0.0% | >1,000 |

| Uranium | PJ | 2, 5 | 749,840 | 1.7 | 2 | 2,624 | 1.9 | 185,360 | 3.8% | 71 |

| Thorium | kt | 6 | 796 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | - | - |

| Total resources | PJ | 7 | 6,304,862 | -0.1 | 20,691 | -2.7 | 2,885,129 | -0.5% | 139 |

Abbreviations

kt = thousand tonne; LPG = liquefied petroleum gas; PJ = petajoule; TDR = total demonstrated resources.

Notes

1. Total Demonstrated Resources (TDR) = 2P reserves plus 2C contingent resources from the PRMS classification system. 2. Producing basins relates to oil and gas, producing deposits relates to black coal, brown coal and uranium. 3. TDR = demonstrated recoverable coal resources. Reserves = economic demonstrated resources. 4. Coal production data for 2023 is for 2022-23 (DCCEEW, 2024a). 5. Recoverable resources at <US$130/kg. 6 A conversion into energy content equivalent for thorium was not available at the time of publication. 7. Excludes thorium resources.

Source: Geoscience Australia (2024); Hughes et al. (2025); DCCEEW (2024a) Australian Energy Statistics 2024.

Table 1.2 Australia's total demonstrated non-renewable energy resources 2014/16 to 2023

| Resource | Unit | Note | TDR 2014/2016 | TDR 2018 | TDR 2019 | TDR 2020 | TDR 2021 | TDR 2022 | TDR 2023 | 2018–2023 TDR % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude oil | PJ | 1, 2 | 7,066 | 6,474 | 5,661 | 5,205 | 4,546 | 4,791 | 4,555 | -29.6% |

| Condensate | PJ | 1, 2 | 16,463 | 16,213 | 15,951 | 15,448 | 15,581 | 14,787 | 14,534 | -10.4% |

| LPG | PJ | 1, 2 | 5,957 | 1,483 | 1,421 | 1,207 | 1,155 | 1,294 | 1,307 | -11.9% |

| Oil shale | PJ | 1, 2 | 0 | 84,436 | 84,436 | 84,436 | 84,436 | 78,830 | 78,966 | -6.5% |

| Unconventional oil (undifferentiated) | PJ | 1, 2 | 0 | 335 | 335 | 404 | 369 | 841 | 893 | 166.6% |

| Conventional gas | PJ | 1, 2 | 186,235 | 194,239 | 196,133 | 192,252 | 187,839 | 176,710 | 174,625 | -10.1% |

| Coal seam gas | PJ | 1, 2 | 79,450 | 63,732 | 58,248 | 55,131 | 57,316 | 56,348 | 55,867 | -12.3% |

| Coal seam gasification | PJ | 1 | na | 1,469 | 2,622 | 2,622 | 2,622 | 2,622 | 2,622 | 78.5% |

| Unconventional gas (undifferentiated) | PJ | 1, 2 | 14,000 | 13,426 | 12,203 | 12,252 | 10,194 | 14,541 | 14,313 | 6.6% |

| Black coal | PJ | 3, 4 | 1,999,669 | 2,066,612 | 2,085,362 | 2,021,599 | 2,046,714 | 1,975,942 | 1,959,440 | -5.2% |

| Brown coal | PJ | 3, 4 | 3,250,352 | 3,293,660 | 3,240,107 | 3,247,899 | 3,247,899 | 3,247,899 | 3,247,899 | -1.4% |

| Uranium | PJ | 4, 5 | 718,083 | 801,287 | 673,791 | 737,923 | 732,480 | 737,520 | 749,840 | -6.4% |

| Thorium | kt | 4, 6 | 130 | 130 | 560 | 635 | 604 | 795 | 796 | 512.3% |

| Total resources | PJ | 7 | 6,277,275 | 6,543,366 | 6,376,270 | 6,376,378 | 6,391,151 | 6,312,125 | 6,304,862 | -3.6% |

Abbreviations

kt = thousand tonne; LPG = liquefied petroleum gas; PJ = petajoule; TDR = total demonstrated resources.

Notes

1. Total Demonstrated Resources (TDR) = 2P reserves plus 2C contingent resources from the PRMS classification system. 2. Oil and gas data for the end 2014 are as reported by Geoscience Australia (2018). 3. Demonstrated recoverable coal resources. 4. Coal, uranium and thorium data for the end of 2016 are as reported by Geoscience Australia (2018). 5. Recoverable resources at <US$130/kg. 6. A conversion into energy content equivalent for thorium was not available at the time of publication. 7. Excludes thorium resources.

Source: Geoscience Australia (2024); Hughes et al. (2025).

Box 1.1 Energy resource estimates and terminology

Estimating energy resource volumes requires a consistent approach to describing commodity reserves and resources to ensure results are reliable and easily comparable. Appendix 3 outlines the various resource classification systems used in AECR to describe the commerciality of energy resources. These systems use levels of geological knowledge and confidence to distinguish between identified and potential resources.

For the purposes of the AECR publication the following terminologies are used to describe the various energy resource classifications:

Identified resources are those for which measurements have been made to quantify their extent and grade or quality. A measurement may be, for example, a well drilled into an oil reservoir to provide a sample. The process of ‘proving’ that a resource is suitable for development is one of reducing uncertainty through the measurement of the nature of the resource, and its commercial and social viability.

‘Reserves’ and ‘economic demonstrated resources (EDR)’ are terms given to non-renewable energy resources that are known to exist in sufficient quantity and grade confirming their commercial and social viability. ‘Contingent resources’ or ‘sub economic resources’ are the terms given to resources that have been confirmed to exist and are potentially recoverable, but not yet considered mature enough for commercial development or are not currently viable and/or economic to extract. Total demonstrated resources (TDR) is the sum of these two resource classes.

‘Potential resources’ are identified by indirect evidence with a high degree of uncertainty around their existence and viability. The potential resource base is often described by the terms ‘prospective’, ‘undiscovered’ or ‘inferred’. These potential resources require further exploration programs to demonstrate if a resource is present, followed by appraisal programs to determine the economic and technical viability of extracting any identified resources.

Furthermore, the resource base cannot be considered in isolation from energy conversion technologies. For example, energy security increased globally when the advancement of hydraulic fracturing technologies enabled once non-viable shale oil and shale gas resources in the US to be commercially exploited.

Estimating the resource base requires setting a cut-off grade—for example, a minimum estimated ultimate recovery of gas in a reservoir for conventional hydrocarbons or well drainage area for unconventional hydrocarbons. An energy conversion technology is implicit in this—hence, the minimum viable resource is determined not only by the inherent nature of the resource, but also by the technology available to produce it.

Due to their risk and uncertain nature, only a limited set of prospective resource estimates are published each year by energy companies. Consequently, it is not possible to provide a complete aggregation of all prospective gas resources in Australia using published prospective resource estimates.

Mineral and petroleum energy resource estimates are often documented as industry standard measurements of volume or mass. Coal and uranium are generally measured by weight (tonnes), while oil and gas are generally measured by volume (barrels/cubic feet). However, the energy content of different energy commodities varies significantly. In this assessment, energy resource estimates have been converted to a common energy unit—petajoules (PJ)—to allow direct comparisons of different energy commodities. Appendix 5 provides measurement units, average energy contents and conversion factors for the various energy commodities.

Changes in resources estimates can usually be attributed to one, or a combination, of the following factors:

- Increases in resources resulting from discoveries of new accumulations or deposits and delineation of extensions of known resources.

- Depletion of resources as a result of production.

- Advances in extraction techniques and technologies, enabling economic extraction of resources previously deemed uneconomic.

- Significant changes in energy commodity prices, driven largely by global trends in the supply and demand of energy resources.

Estimating energy reserve life

The potential life of Australia’s non-renewable energy reserves is estimated through dividing the total remaining identified reserves by 2023 annual production rates. Such estimates provide a snapshot in time that can only be used for general impressions as they are averages based on the assumption that:

- future production rates remain the same as the 2023 production rates used in the calculation.

- accumulations and deposits deemed as identified reserves in 2023 will remain so in the future and not be reclassified as identified, prospective or contingent resources; and

- depleted reserves are not replaced by new discoveries or conversion of contingent resources to reserves.

Gas resources

Australia has substantial conventional gas resources that are located mostly off the northwest coast of Western Australia, and significant onshore unconventional resources (coal seam gas, shale gas, and tight gas). In 2023 Australia’s TDR for its conventional and unconventional gas is estimated at 247,427 PJ (220 trillion cubic feet [Tcf]), of which 106,301 PJ (95 Tcf) are classified as proven and probable (2P) reserves.

In 2023, Australia’s TDR for conventional gas is estimated to be 174,625 PJ (155 Tcf), a decrease of 1.2% from 2022. This decrease continues the trend of natural field decline seen since 2019 as conventional gas production exceeds the discovery rate for new resources. At 2023 production rates, the estimated life for Australia’s conventional gas reserves (74,586 PJ; 66.3 Tcf) is 16 years. Most of the remaining identified conventional gas resources occur in basins on Australia’s North West Shelf.

Coal seam gas (CSG) resources are located in Australia’s east in the Bowen, Surat, Galilee and Gunnedah basins. In 2023, TDR for Australia’s CSG are estimated at 55,867 PJ (49.7 Tcf), a decrease of 0.9% from 2022. At 2023 production rates, Australia’s 30,562 PJ (27.2 Tcf) of CSG reserves has an estimated life of 19 years.

Prospective shale gas, tight gas and basin centred gas resources are held in low permeability reservoirs across Australia. Most of these resources are located in the Cooper Basin, Canning Basin, Bowen/Surat basins and Beetaloo Sub-basin. In 2023, TDR for unconventional gas (excluding CSG and in-situ coal seam gasification) totalled 14,313 PJ (12.7 Tcf), representing a 1.6% decrease from 2022. There were no identified unconventional gas reserves in 2023 and due to the lack of production there is no resource life estimation for these unconventional gas resources.

Oil resources

Australia’s conventional liquid hydrocarbon resources include crude oil and the condensate plus liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) resources associated with gas accumulations (as phases of natural gas liquids). Australia also has significant unconventional oil resources, although these are currently undeveloped. In 2023 Australia’s TDR for all oil resources are estimated at 100,255 PJ (17,142 million barrels [MMbbl]), of which 7,551 PJ (1312 MMbbl) are classified as proven and probable (2P) reserves. Approximately 80% of these resources are associated with unconventional oil shale deposits. Australia is reliant on crude oil and refined petroleum imports to meet its energy requirements, importing about 96% of our crude oil and refined oil products.

Australia’s crude oil resources are small by world standards and are being depleted at a faster rate than they are being replenished by new discoveries. In 2023, TDR for Australia’s crude oil is estimated to be 4,555 PJ or 775 MMbbl, down 4.9% (234 PJ) from 2022, with notable declines in the Northern Carnarvon/Roebuck and Bowen/Surat basins, and increases in the Perth and Bonaparte/Browse basins. Based on 2023 production rates, the estimated life for Australia’s crude oil reserves is 7 years.

Australia’s liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) resources are also relatively small with an estimated TDR of 1,307 PJ (310 MMbbl) in 2023, an increase of 1.0% from 2022. Based on 2023 production rates, the remaining life for Australia’s LPG reserves is about 10 years. Australia has significantly more condensate than crude oil and LPG resources, with an estimated TDR of 14,534 PJ (2,472 MMbbl) in 2023, a decrease of 1.7% from 2023. Most condensate resources are associated with LNG projects in the Northern Carnarvon and Browse basins on the North West Shelf. Based on 2023 production rates, these condensate reserves have an estimated life of about 15 years.

Unconventional oil resources are currently undeveloped and include oil shale occurrences (TDR of 78,966 PJ; 13,430 MMbbl) and minor condensate and LPG associated with unconventional gas resources (TDR of 893 PJ; 155 MMbbl). Currently there are no unconventional oil reserves or production in Australia.

Coal resources

Australia’s coal resources are world class in terms of volume and quality. As of December 2023, TDR for Australia’s recoverable black and brown coal are estimated to be 5,207,339 PJ (409,174 million tonnes [Mt]). In addition to having a large TDR of coal, Australia also has significant Inferred coal resources.

TDR for black coal is estimated to be 1,959,440 PJ (77,750 Mt). Black coal resources are found in most states, with the largest TDR in the Bowen–Surat basins in Queensland and the Sydney Basin in New South Wales. In 2023, Australia’s black coal TDR decreased by 0.8% and Economic Demonstrated Resources for black coal fell by 0.9% (Hughes et al., 2025).

Australia has vast brown coal resources, although these have a much lower energy content than black coal. Brown coal TDR are estimated to be 3,247,899 PJ (331,423 Mt) and are located mainly in Victoria’s Gippsland Basin. Australia’s brown coal reserves remain unchanged since 2021.

At 2023 production rates, Australia’s coal resources are sufficient to support many decades of production, well beyond the targeted phase out of coal as a major source of energy in Australia (DCCEEW, 2025a).

Uranium and thorium resources

Australia hosts the largest uranium resources in the world with more than one-third of the world’s known uranium resources. As of December 2023, TDR for Australia’s uranium resources are estimated to be 749,840 PJ (1,339 thousand tonnes [kt]). Although most Australian jurisdictions host uranium deposits, the largest known resources are concentrated in South Australia, the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Australia’s TDR for uranium resources showed a minor increase of 1.7% in 2023.

Australia also has a major share of the world’s thorium resources, which while not currently in use as an energy resource, could play a role as a nuclear energy source in the future. In 2023, Australia’s total identified in situ thorium resources were approximately 1,433 kt, most of these resources are associated with heavy mineral sand deposits.

Enabling Clean Energy Technologies

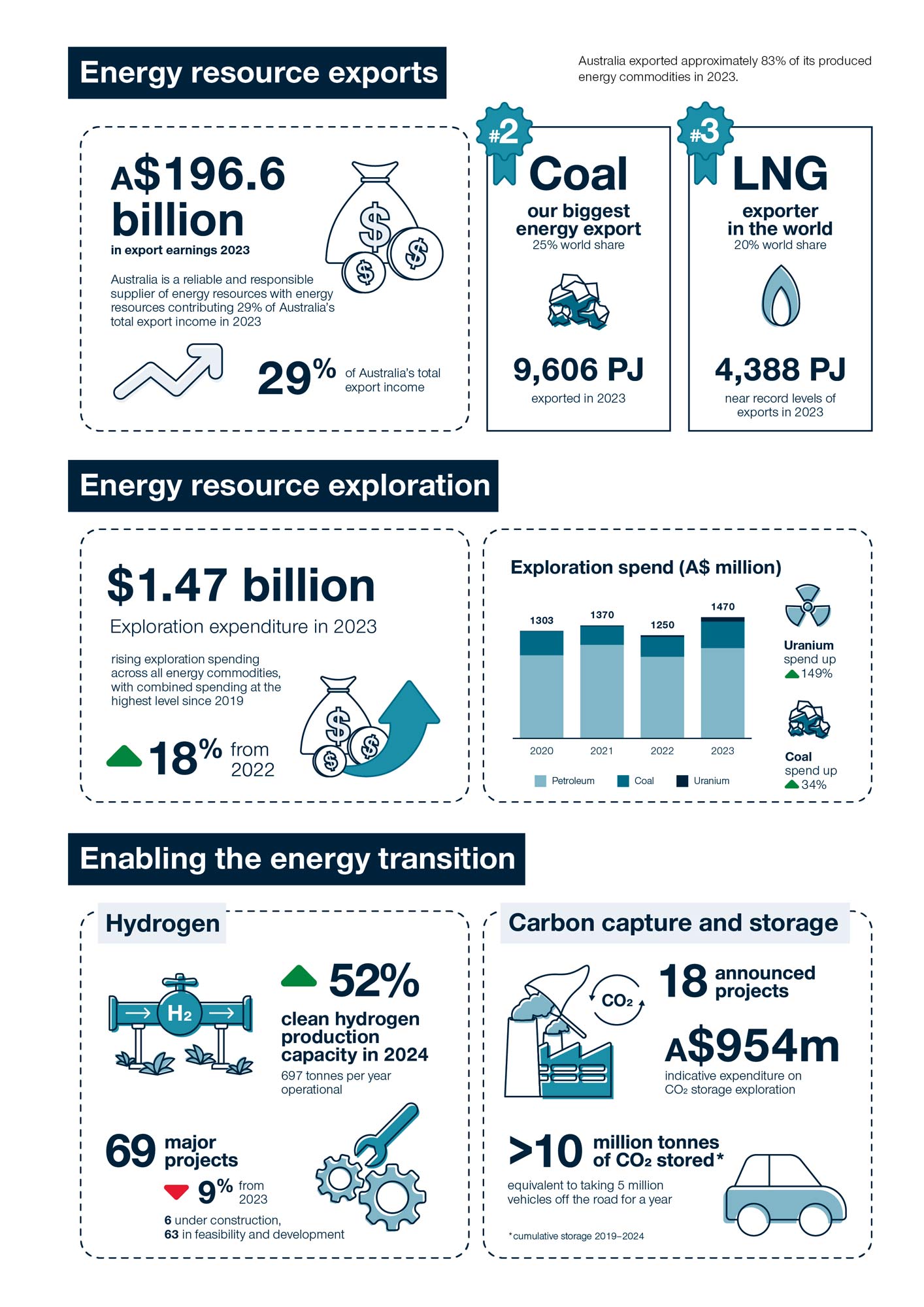

Clean energy technologies are rapidly being developed in Australia to meet emission reduction targets, including renewable energy, carbon capture and storage (CCS), as well as renewable and low emissions hydrogen production.

The Australian Government is committed to reaching net zero emissions by 2050, and in September 2025, released Australia’s Net Zero Plan that sets a national target to reduce emissions by 62–70% below 2005 levels by 2035 (DCCEEW, 2025b). The Net Zero Plan identifies 5 priority decarbonisation actions to reduce key emissions sources across the economy and is supported by six detailed sector plans that aim to ensure a fair and orderly transition to net zero.

The Net Zero Plan and 2035 emissions reduction target builds on the strong foundations laid in the past three years—including the legislated target of a 43% reduction in emissions on 2005 levels by 2030 (DISR, 2022) and the Safeguard Mechanism reforms that set reduced emissions limits for large emitters, including for energy commodity projects (DCCEEW, 2023)—to accelerate progress toward net zero emissions by 2050.

Achieving Australia’s 2035 emissions reduction target can be supported by the deployment of low-emissions technologies, including CCS, hydrogen, renewable energy.

Geothermal energy, though not currently included in the Australian Government’s emissions reduction strategy, is gaining traction internationally as a low emission energy source and has potential to be developed in Australia.

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is a key energy commodity for decarbonising Australia’s economy, particularly for hard-to-abate sectors such as heavy industry, long-haul transport and chemical manufacturing. In September 2024, the Australian Government released the National Hydrogen Strategy 2024, which provides a thorough review and update of the first National Hydrogen Strategy published in 2019. The revised strategy focusses on the growth of clean hydrogen industry and aims to position Australia as a global leader in the production, use and export of hydrogen. A key component of the updated Strategy, announced as part of the Government's Future Made in Australia plan in the 2024-25 Federal Budget, are production incentives designed to accelerate investment, promote economies at scale and reduce the cost gap for renewable hydrogen. Investment from Australian state/territory and federal governments is increasing, with A$17.5 billion of committed hydrogen specific support and A$42.8 billion of hydrogen eligible support through a range of programs (CSIRO, 2024). The first recipient of the Australian Government’s Hydrogen Headstart Program was announced in March 2025, with $814 million in funding allocated to the 1,500 MW Murchison Green Hydrogen Project in Western Australia.

Australia has extensive world-class renewable and non-renewable energy resources that can support the development of a new clean hydrogen industry. There is significant interest in Australia’s future clean hydrogen production, with the industry moving from pilot and small demonstration projects to the construction of large-scale demonstration projects. Total clean hydrogen production increased by 52% from the previous year to 697 tonnes per year.

In addition to hydrogen production, Australia is prospective for naturally occurring hydrogen resources. Although the geological controls for the occurrence of this resource are not yet completely understood, exploration for hydrogen is expanding, as evidenced by the recent uptake of exploration permits targeting natural hydrogen. In 2024, Australia had an estimated 8 PJ of naturally occurring hydrogen resources.

Carbon Capture and Storage

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and/or carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) is a decarbonisation tool that can be applied to prevent the release of CO2 from stationary greenhouse gas emission sources and to remove CO2 emissions directly from the atmosphere. The CCS value chain includes capturing, transporting, compressing, and injecting CO2 into deep underground geological formations where it is permanently trapped. Together with a range of other decarbonisation solutions, the large-scale implementation of CCS in Australia is widely regarded as necessary for meeting Australian emissions reduction targets.

The CCS landscape in Australia is rapidly evolving. Since 2022, there has been considerable activity with respect to the legislative and regulatory frameworks that govern and enable CCS in Australia. There are now frameworks enabling greenhouse gas storage in place in South Australia, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia as well as in the offshore Commonwealth jurisdiction. In 2023, the Environment Protection (Sea Dumping) Amendment Act 2023 (Using New Technologies to Fight Climate Change) came into force, providing a framework to enable the transboundary movement (international import or export) of CO2 for the purpose of sub-seabed geological storage.

As of June 2025, there are 18 commercial CO2 storage projects across Australia, plus several research facilities and programs. Two of these are operational, commercial-scale CCS facilities: the Gorgon CCS Project and the Moomba CCS Project. The Gorgon CCS Project has been operating since 2019 and as of May 2025 had stored more than 11 million tonnes (Mt) of CO2.The Moomba CCS became operational in late September 2024, and by mid-July 2025 had stored 1 Mt of CO2-equivalent. There are now 17 Commonwealth Offshore Greenhouse Gas Storage assessment permits, 10 of which were awarded in 2024, following their release in 2023. The 17 permits are located in the Bonaparte, Browse, Northern Carnarvon, Perth, Otway, Bass and Gippsland basins and have total indicated work program commitments of approximately $1 billion. In 2024, Australia’s reported demonstrated CO2 storage resources (2P capacity and 2C contingent resources) were 674 Mt CO2., with a further estimated 31 gigatonnes (Gt) of sub-commercial (theoretical) CO2 storage resources.

Geothermal energy

Geothermal energy is a form of renewable energy that comes from the natural heat stored beneath the Earth's surface. It is not variable and does not require energy storage to provide a constant supply of electricity or heat. Australian geothermal installations include many ground-source heat pumps, mostly installed in the colder regions of Australia, and numerous direct-use installations, largely located in the Perth, Otway, Gippsland and Great Artesian basins.

The geothermal energy sector in Australia is in the early stages of development. The development of geothermal energy for utility-scale electricity generation remains limited to previous small-scale trial projects in Australia, but has recently experienced a resurgence of interest, as evidenced by a substantial increase in permit applications across the country in recent years.

- The uptake of exploration permits continues to grow, with a 12% increase in granted (28) and under-application (96) exploration permits in Australia in the 12 months to December 2024.

- Australia’s largest geothermal system began operating at the Australian War Memorial in October 2024.

Recent international breakthroughs in geothermal drilling technology have the potential to positively impact on the future development of geothermal energy in Australia.

References

CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation), 2024. HyResource - Funding. (Last accessed August 2025).

DCCEEW (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water), 2023. Safeguard Mechanism.

DCCEEW (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water), 2024a. Australian Energy Update 2024

DCCEEW (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water), 2024b. National Hydrogen Strategy 2024.

DCCEEW (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water), 2025a. Electricity and Energy Sector Plan, 2025.

DCCEEW (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water), 2025b. Australia’s Net Zero Plan, 2025.

DISR (Department of Industry, Science and Resources), 2022. Australia’s Nationally Determined Contribution: Communication 2022.

Energy Institute, 2024. Statistical Review of World Energy.

Geoscience Australia, 2024. Australia’s Energy Commodity Resources, 2024 Edition. Geoscience Australia, Canberra.

Hughes, A., Britt, A., Pheeney, J., Morfiadakis, A., Kucka, C., Colclough, H., Munns, C., Senior, A., Cross, A., Hitchman, A., Cheng, Y., Walsh, J., and Jayasekara, A., 2025. Australia’s Identified Mineral Resources 2024. Geoscience Australia, Canberra.

Data download

Data tables and full report are downloadable from the Geoscience Australia website.