Australia's Energy Commodity Resources 2025 Uranium and Thorium

Page last updated:23 October 2025

Uranium and Thorium

Uranium

|

TDR 749,840 PJ ( 1.7%) | |

|

EDR 705,600 PJ ( 1.9%) |

|

Production 2,624 PJ ( 2.9%) | |

|

Exports 2535 PJ ( 1.6%) $0.9 b ( 25%) |

|

Production World Ranking 4 (9%) | |

|

Export World Ranking na |

Notes

Statistics are for 2023, percentage increases or decreases are in relation to 2022. World rankings are followed by percentage share in brackets. TDR – Total Demonstrated Resources; EDR – Economic Demonstrated Resources; PJ – petajoules; $b – billion dollars (Australian); na – not available.

Highlights

- Australia plays a significant role in the global uranium market despite the absence of domestic nuclear power. Australia contains the world’s largest resources of uranium and is the fourth largest producer despite mining of uranium currently only being permitted in South Australia and the Northern Territory. Australia’s uranium industry has seen further growth amid increasing global interest in nuclear energy as an alternative low-emission power source.

- In 2023, Australia had two producing uranium mines: Olympic Dam and Four Mile, both in South Australia. The Olympic Dam Mine remains the world’s largest deposit of uranium. The Honeymoon Mine, also in South Australia, recommenced operations in late 2023 (producing in 2024) after being in care and maintenance since 2013.

- Australia exports all its uranium production to countries which have signed bilateral safeguards agreement, ensuring that Australian uranium is only used for peaceful purposes and does not contribute to any military applications. Australia’s average annual export volume of uranium for the last 10 years is approximately 5,550 tonnes of uranium (tU).

- Uranium exploration spending has risen solidly in recent years, from its low in 2019–2020, total exploration expenditure in 2023 was $55 million, the highest level in a decade (ABS, 2024).

- Australian commonwealth legislation does not permit the establishment of a nuclear power industry in Australia. Australian uranium production is not used for power generation in Australia.

- Thorium has been used previously in the nuclear generation process, but its use is still largely experimental and there is no current commercial market for thorium.

- Thorium is not produced in Australia and production on a large scale is unlikely in the immediate future.

Uranium

In its native form, Uranium is a slightly radioactive element that is widespread at levels of 1 to 4 parts per million (ppm) in the Earth’s crust. Concentrations of uranium-rich minerals, such as uraninite, carnotite and brannerite, can form economically recoverable deposits. The majority of Australia's uranium occurs in four main types of deposit: iron oxide breccia complexes, unconformity-related accumulations, sandstone-hosted resources and palaeochannel/calcrete-style resources.

Once mined, uranium is processed into uranium oxide (U3O8), also referred to as uranium oxide concentrate and is exported in this form. Natural uranium (from mine production) contains approximately 0.7% of the uranium isotope 235U and 99.3% 238U.

Uranium resources

Australia’s uranium resources are expressed as Economic Demonstrated Resources (EDR), Subeconomic Demonstrated Resources (SDR) and Inferred Resources. Refer to Appendix 3 for definitions of these terms and further information on the National Classification System for reporting of Identified Mineral Resources.

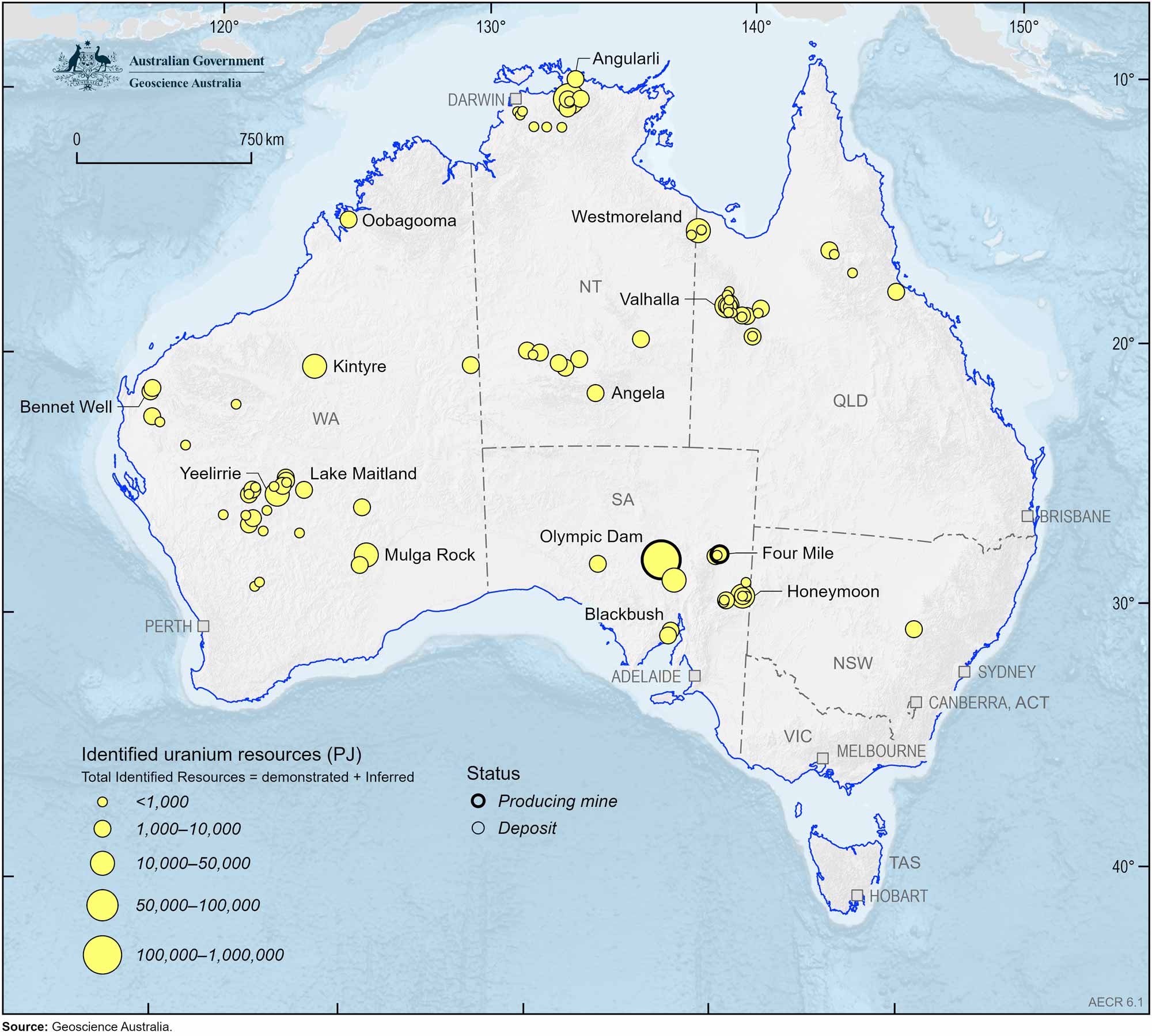

Accounting for more than one-third of the world’s known uranium resources, in 2023 Australia’s total Identified Resources (EDR plus SDR plus Inferred Resources) were 1,960 ktU (1,097,600PJ)—comprising 1,260 ktU (705,600 PJ) of EDR, and 79 ktU (44,240 PJ) of SDR and 621 ktU (347,760 PJ) of Inferred Resources. Although most Australian states and territories host uranium deposits, EDR of uranium are concentrated in South Australia, the Northern Territory and Western Australia (Figure 6.1). South Australia’s Olympic Dam is the world’s largest uranium deposit, with an EDR of 987 ktU (553,219 PJ). Based on 2023 production rates, Australia’s uranium reserves have an estimated life of 71 years.

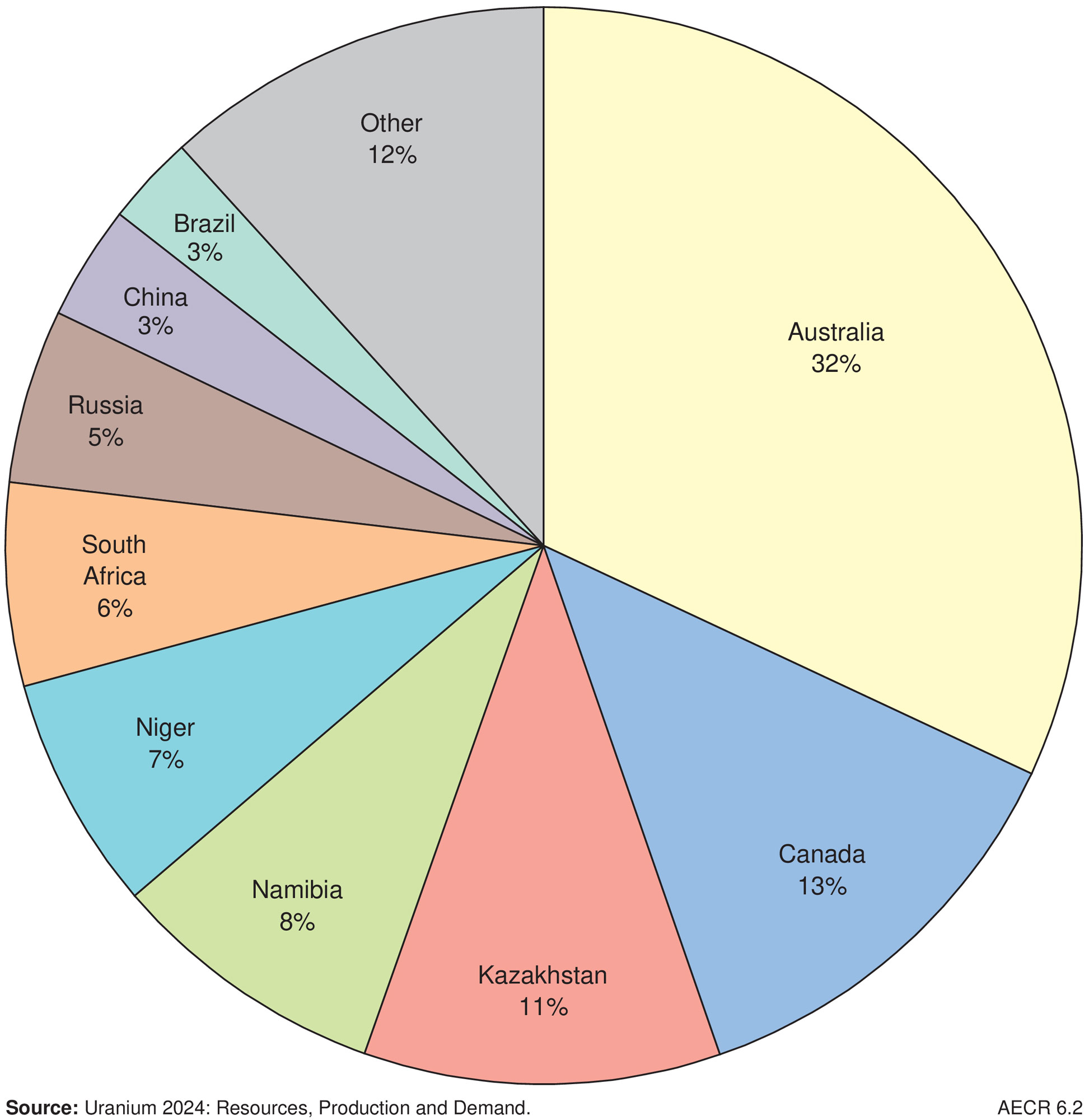

The recoverable volumes of World Reasonably Assured Resources (RAR) at less than US$130/kgU were estimated at approximately 3,869 million tonnes (Mt) in 2024 (OECD NEA and IAEA, 2025). Australia accounts for approximately 32% of this global inventory (Figure 6.2).

Production and trade

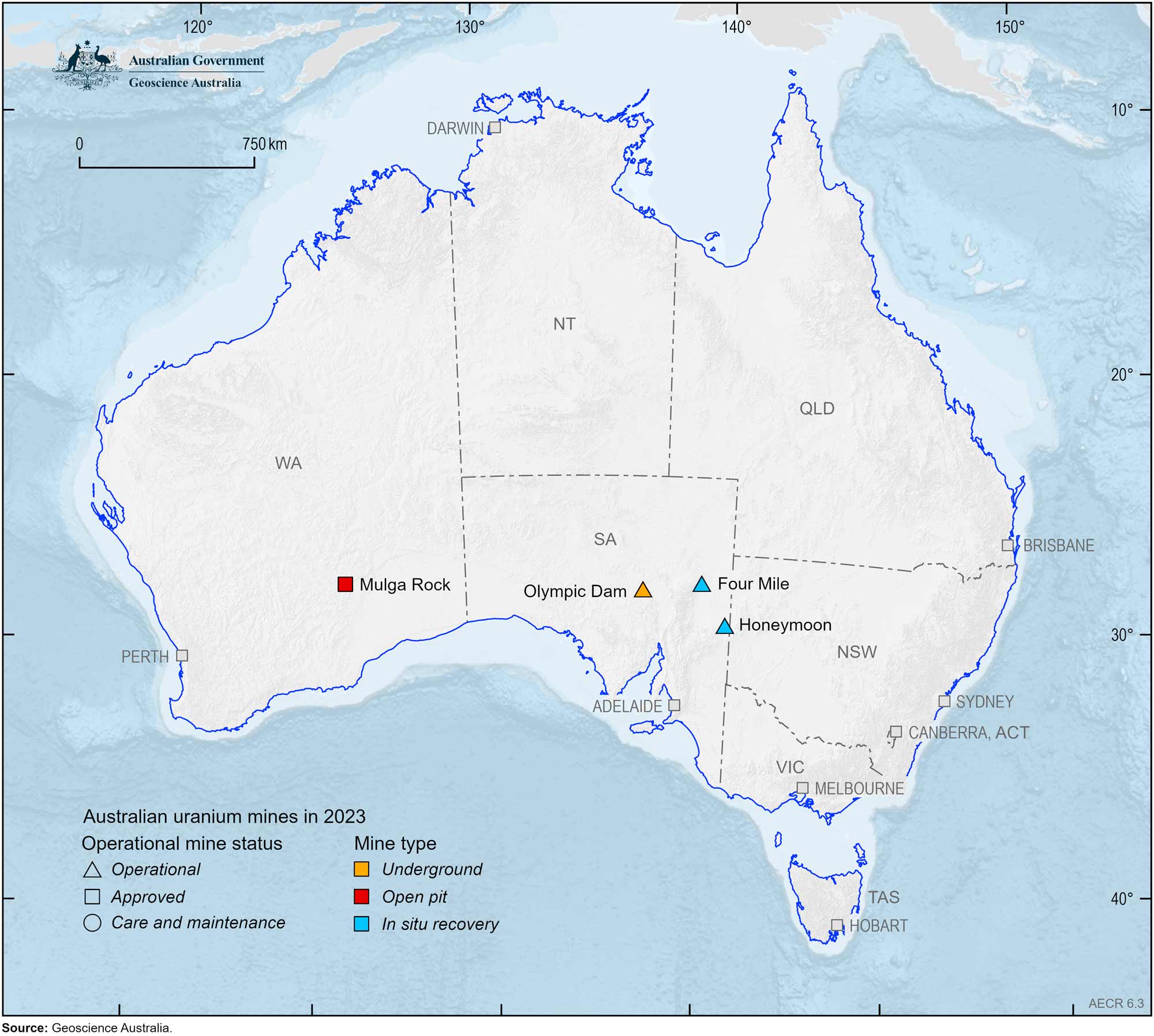

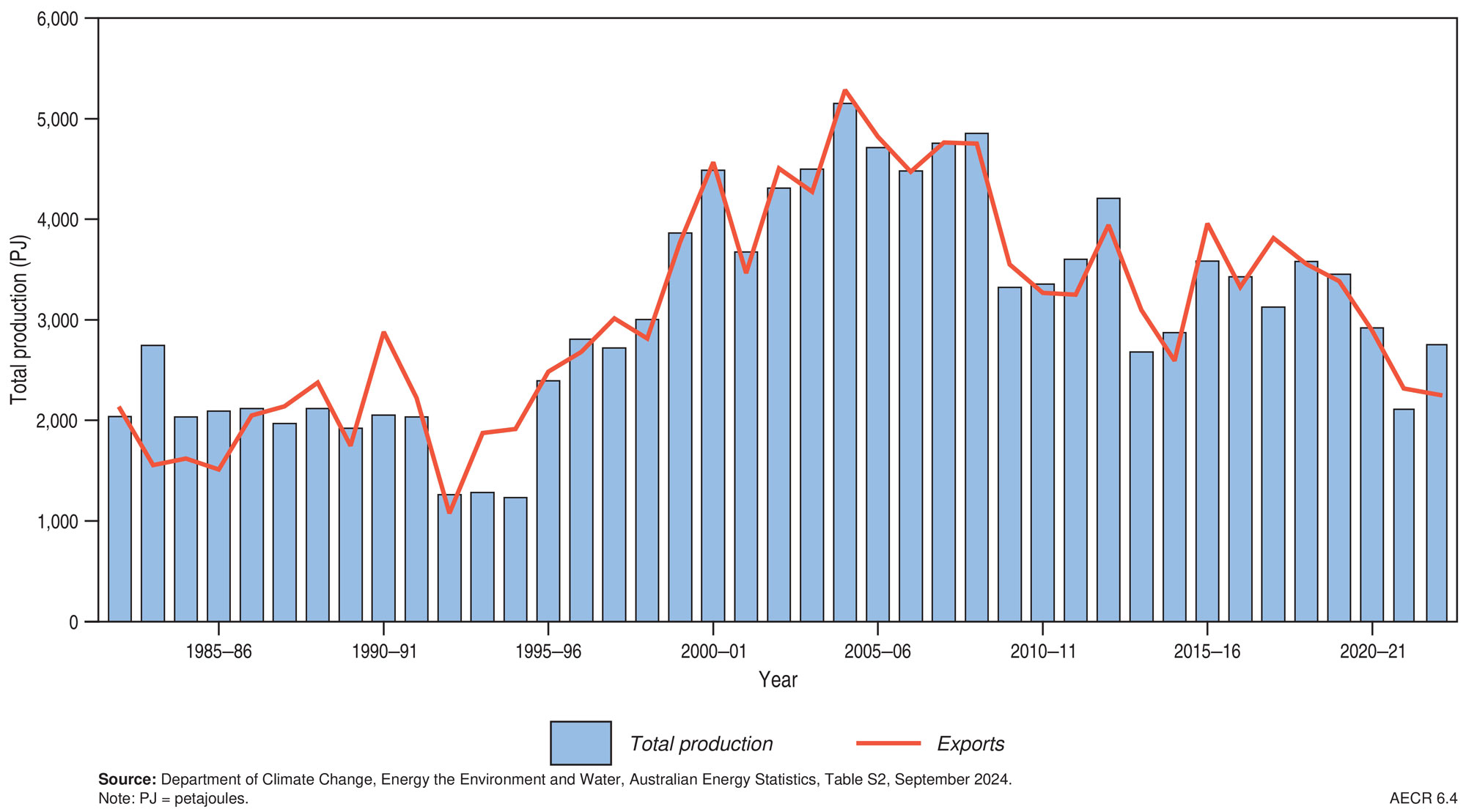

Global uranium production is dominated by a few countries, with Australia, Kazakhstan, Canada, Namibia, South Africa and Niger accounting for most production. In 2023, Australia ranked as the 4th largest uranium producer, contributing 9% of global production with 4,686 tU (2,624 PJ; Figure 6.4) produced from the Olympic Dam and Four Mile mines (Figure 6.3). Production increased modestly in 2023, up 3% from 2022, and Australia’s uranium production is projected to continue growing to 2030 (DISR, 2025).

The Honeymoon Mine in South Australia (Boss Energy), which had been in care and maintenance since 2013, re-commenced mining operations in the December quarter 2023, with production starting in 2024 (Figure 6.3). In Western Australia, the Mulga Rock Project (Deep Yellow Ltd.) acquired environmental approval in 2017 and commenced a revised Definitive Feasibility Study (DFS) in 2024. Production is planned to commence in 2028.

Australian mining companies supply uranium under long-term contracts to electricity utilities in North America, Europe and Asia. In 2023, Australia exported 2,535 PJ (4,526 tU; Figure 6.4; DISR, 2025) to Canada (38%), France (23%) and the United States (40%; ASNO, 2024).

Thorium

Australia has a major share of the world’s thorium resources, which while not currently in use as an energy resource, could play a role as a nuclear energy source in the future.

Thorium is a naturally occurring slightly radioactive metal that is three to five times more abundant in the Earth’s crust than uranium. It is less conducive to nuclear weapons proliferation and due to its greater energy-producing efficiency, generates substantially less radioactive waste. The most common source of thorium is monazite, a rare earth phosphate mineral that is a minor constituent of heavy mineral sand (HMS) deposits. On average, monazite contains approximately 6% thorium and 60% rare earth elements.

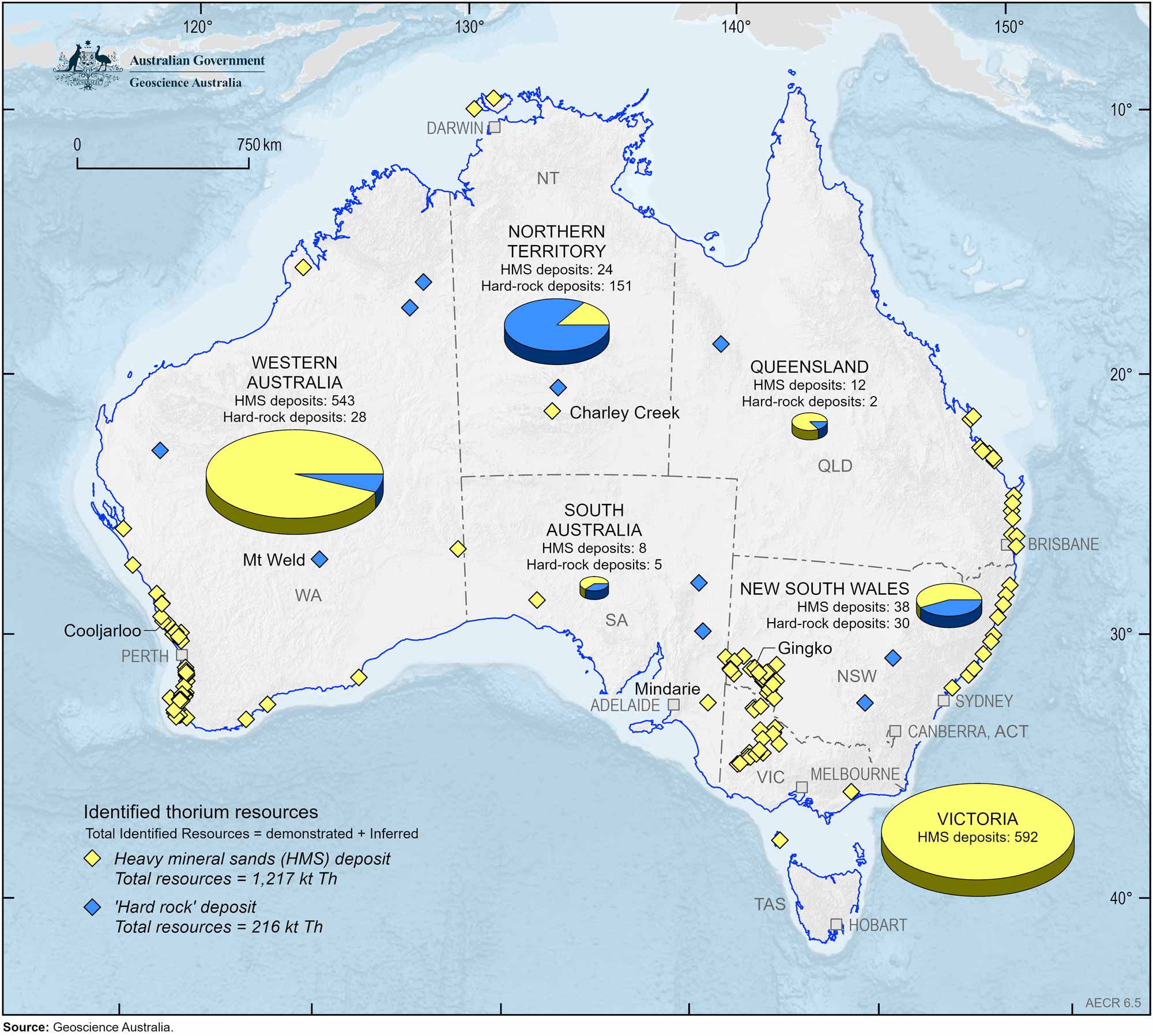

Figure 6.5 Australia’s identified thorium resources in heavy mineral sand and ‘hard rock’ deposits, 2023.

In Australia, approximately 80% of thorium resources are contained in HMS deposits; the remaining 20% are contained in hard-rock rare earth element deposits (Figure 6.5). Monazite and thorium resources are typically not published publicly; however, Geoscience Australia estimates the monazite (and hence thorium) content in deposits and classifies these estimated resources as Inferred Resources. Using this approach, Geoscience Australia estimates that Australia’s total identified in situ thorium resources were approximately 1,433 kt as of 31 December 2023, including 216 kt of ‘hard rock’ resources and 1217 kt of HMS resources.

Although heavy mineral sand (HMS) deposits containing monazite are currently being mined in Australia, thorium is not recovered due to the absence of a commercial market for the element.

Commercial use of thorium as a nuclear reactor fuel is still some decades away, with only small scale and intermittent research into associated technologies. However, thorium-fuelled reactors have previously operated to generate electricity in Germany and the United States (World Nuclear Association, 2020), while India has an operational test facility in operation with plans for a network of larger commercial facilities (World Nuclear Association, 2024; Power, 2019). Extracting the latent energy value of thorium in a cost-effective manner requires considerable investment in research and development (World Nuclear Association, 2020). Thorium can also only be used as a fuel in conjunction with a fissile material such as recycled plutonium.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics), 2024. Mineral and Petroleum Exploration, Australia, Table 5. Released 4 March 2024

ASNO (Australian Safeguards and Non-Proliferation Office), 2024. Australian Safeguards and Non-Proliferation Office, Annual Report 2023-2024.

DISR (Department of Industry, Science and Resources), 2025. Resources and Energy Quarterly: March 2025.

DCCEEW (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water), 2024. Australian Energy Update 2024, Table S, August 2024.

Hughes, A., Britt, A., Pheeney, J., Morfiadakis, A., Kucka, C., Colclough, H., Munns, C., Senior, A., Cross, A., Hitchman, A., Cheng, Y., Walsh, J., and Jayasekara, A., 2025. Australia’s Identified Mineral Resources 2024. Geoscience Australia, Canberra.

OECD, NEA and IAEA (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Nuclear Energy Agency, and International Atomic Energy Agency), 2025. Uranium 2024: Resources, Production and Demand.

Power, 2019. Indian-designed nuclear reactor breaks record for continuous operation (last accessed May 2025).

World Nuclear Association, 2020. Thorium (last accessed May 2024).

World Nuclear Association, 2024. Nuclear Power in India (last accessed May 2025).

Data download

Data tables and full report are downloadable from the Geoscience Australia website.