Key messages

- Uranium and thorium are naturally occurring elements that are widespread in the Earth's crust. Mining occurs in locations where such elements are naturally concentrated.

- To produce nuclear fuel from uranium ore, the uranium is extracted from the host rock and then the 235U isotope is progressively enriched.

- Australia has the world’s largest Economic Demonstrated Resources of uranium and in 2021 was the world’s 4th largest uranium producer. However, Australia has no commercial nuclear power plants and has very limited domestic uranium requirements.

- Australia’s average annual export volume of uranium for the last 10 years is approximately 5,910 tonnes (tU). However, in the medium term, Australia’s uranium exports will drop by approximately 20 per cent due to the Ranger mine ceasing operations in January 2021.

- Thorium has been used previously in the nuclear generation process but its use is still largely experimental and there is no current commercial market for thorium.

- Thorium is not produced in Australia and production on a large scale is unlikely in the immediate future.

Summary

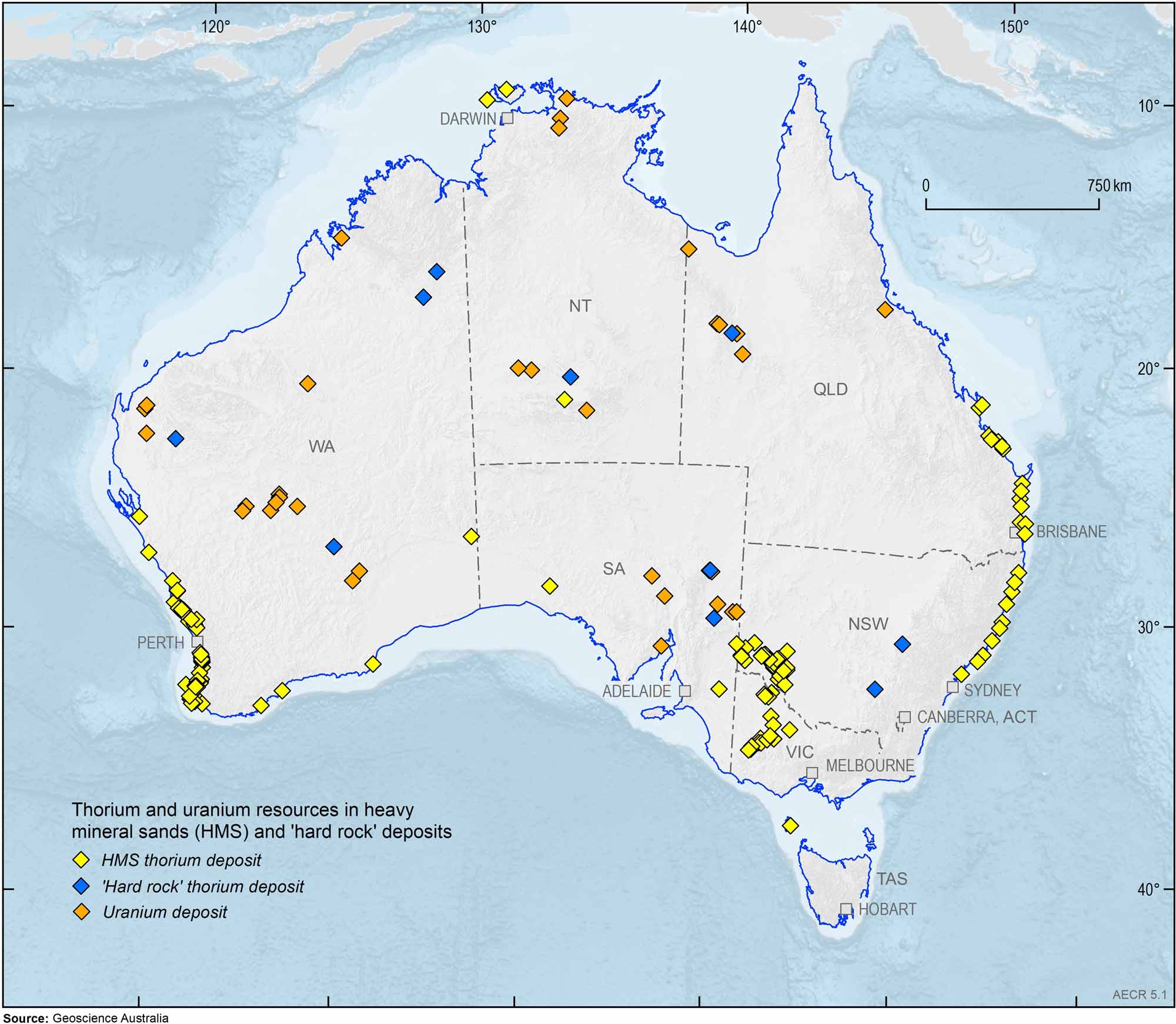

Australia has widespread uranium- and thorium-bearing mineral deposits and has been involved in the uranium industry from its beginnings (Figure 1). The Olympic Dam mine in South Australia remains the world’s largest deposit of uranium.

In January 2021, the historic Ranger mine ceased production after 40 years of operation. Producing approximately 112,000 tU (132,000 tonnes U3O8), it stands as Australia’s largest uranium producer. The Ranger mine is located in the Alligator Rivers region, Northern Territory and is operated by Energy Resources of Australia (ERA; majority owner Rio Tinto with 86.3%). Mining operations ceased in 2012, with production between 2013 and 2021 occurring from stockpiled ore. Rehabilitation of the mine area is currently scheduled to be completed by January 2026.

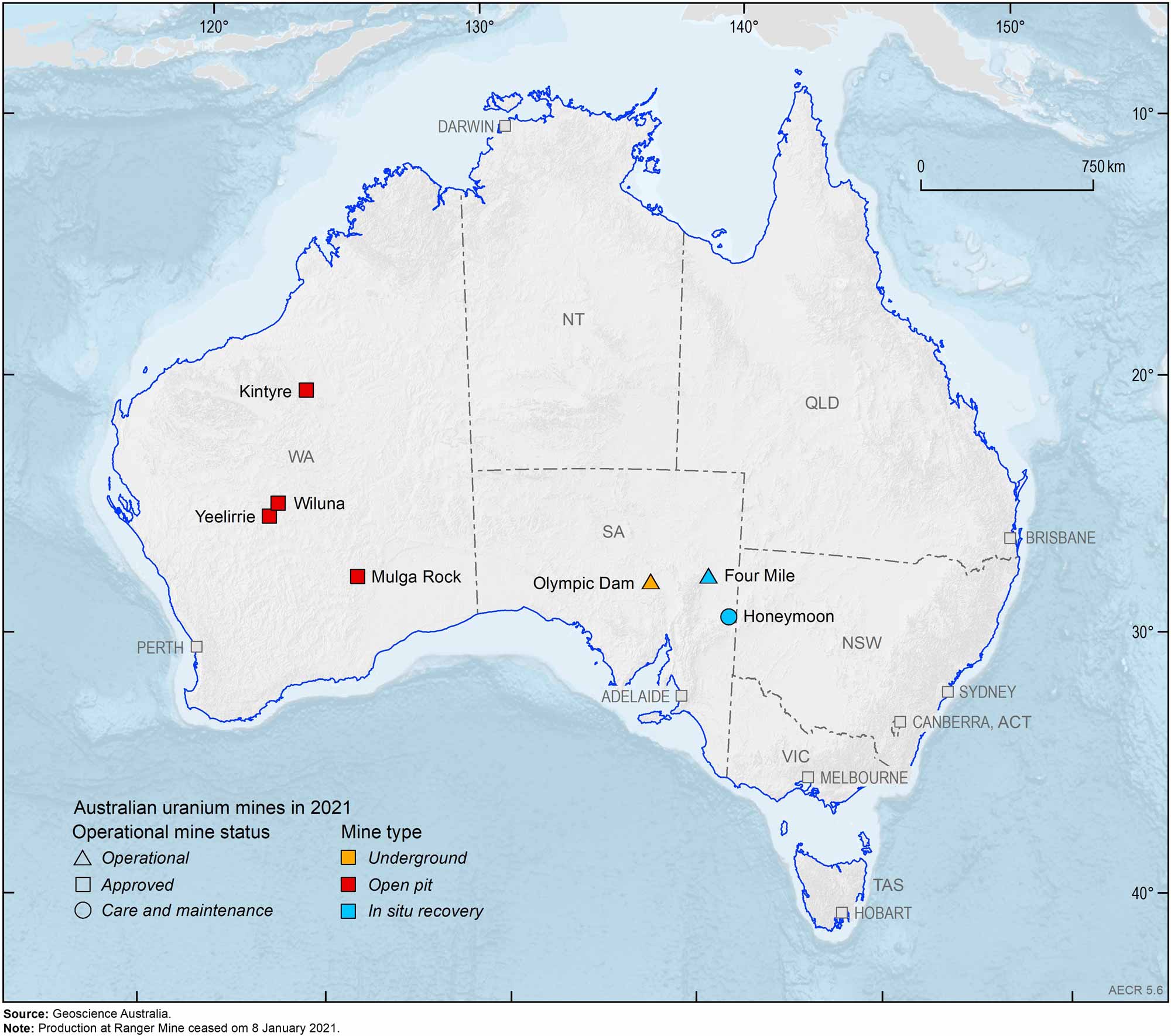

As at 31 December 2021, Australia has the world’s largest Economic Demonstrated Resources (EDR) of uranium—1,227 thousand tonnes of uranium (ktU; 687,120 petajoules [PJ])—and in 2021 was the world’s 4th largest producer of uranium, behind Kazakhstan, Namibia and Canada. In 2021, Australia had two producing uranium mines: Olympic Dam and Four Mile, both in South Australia. Australian supply of uranium is set to decrease by approximately 20 per cent in the medium term, due to the closure of the Ranger Mine in January 2021.

Exploration expenditure for uranium was in decline after the crash of the uranium price in 2011, following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. Additionally, bans and uncertainties concerning uranium mining in some states continue to affect Australia’s ability to attract investment in uranium exploration. However, investment in uranium exploration increased by 84 per cent ($12.3 million) in 2021 driven by steadily increasing uranium commodity prices. Furthermore, in 2022, exploration investment jumped again to $21.7 million.

There are currently no commercial applications for thorium and world production and consumption rates are negligible. As such, thorium is not produced in Australia and production on a large scale is unlikely in the immediate future.

At present, Australia has no plans for a domestic nuclear power industry. However, at state level, South Australia in 2015 undertook a Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission and, more recently, the New South Wales Uranium Mining and Nuclear Facilities (Prohibitions) repeal Bill 2019 and the Victorian Inquiry into Nuclear Energy Prohibition (2020). Additionally, at the federal level, an Inquiry into the Prerequisites for Nuclear Energy in Australia by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on the Environment and Energy was undertaken 2019.

Australia’s identified resources

Uranium

Uranium is a mildly radioactive element that is widespread at levels of 1–4 parts per million (ppm) in the Earth’s crust. Concentrations of uranium-rich minerals, such as uraninite, carnotite and brannerite, can form economically recoverable deposits. The majority of Australia's uranium occurs in four main types of deposit: iron oxide breccia complexes, unconformity-related resources, sandstone resources and palaeochannel/calcrete-style resources.

Once mined, uranium is processed into uranium oxide (U3O8), also referred to as uranium oxide concentrate and is exported in this form. Natural uranium (from mine production) contains approximately 0.7 per cent of the uranium isotope 235U and 99.3 per cent 238U.

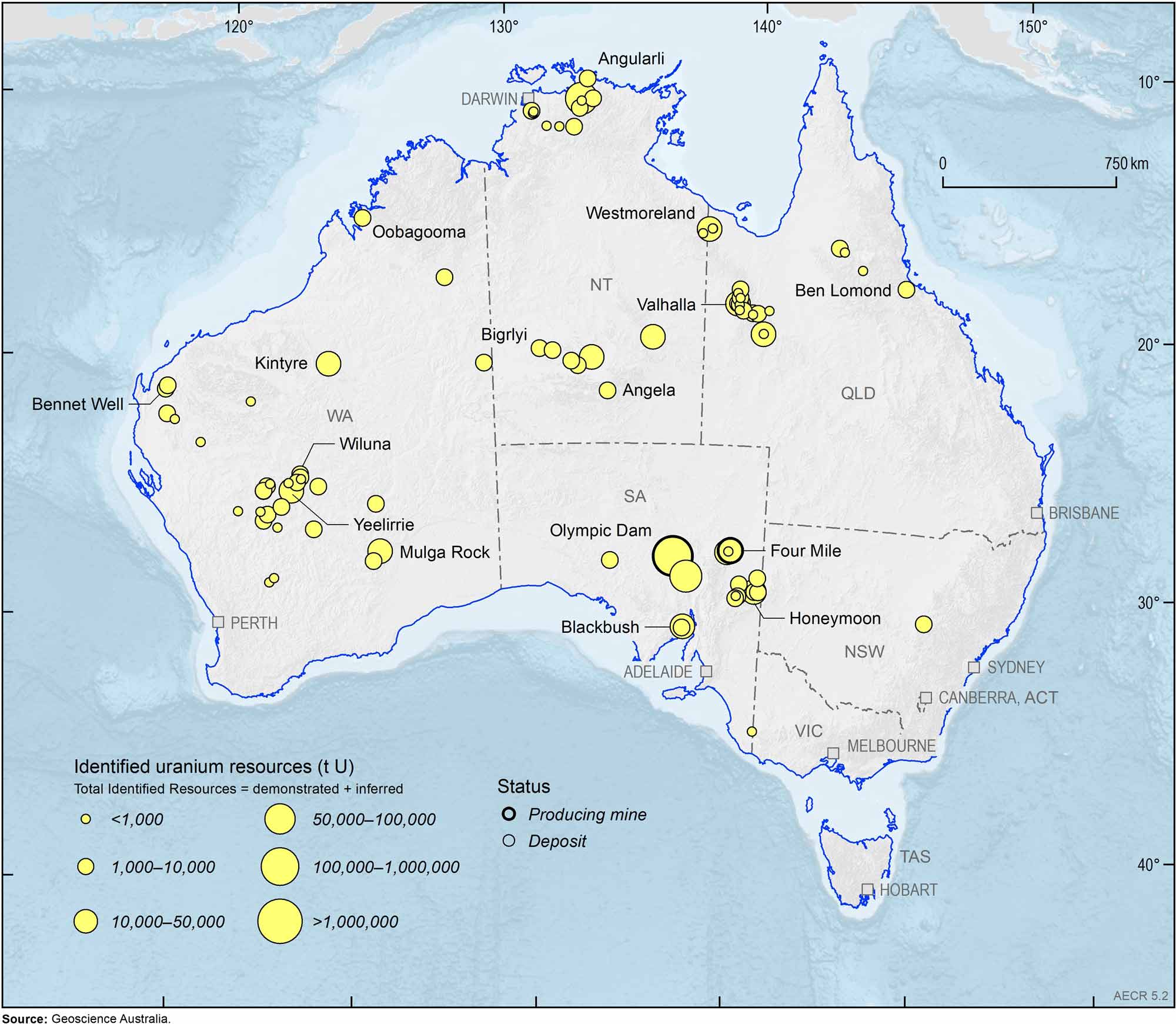

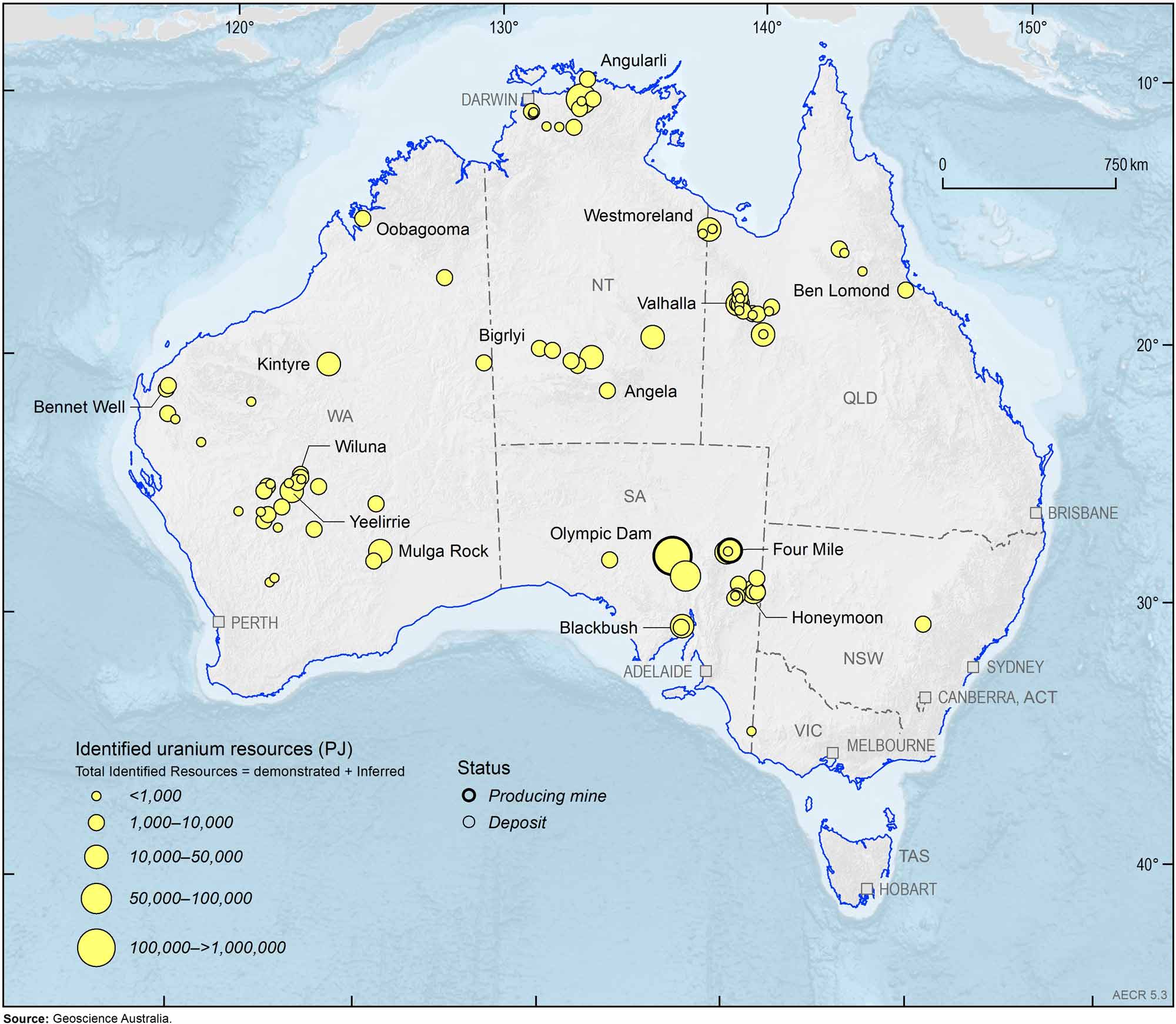

As at December 2021, Australia’s Economic Demonstrated Resource (EDR) for uranium was 1,227 ktU (687,120 PJ). An additional 81 ktU (45,360 PJ) was classified as Subeconomic Demonstrated Resources and 623 ktU (348,871 PJ) as Inferred Resources. Australia’s total Identified Resources were 1,931 ktU (1,081,250 PJ). Although most Australian states and territories host uranium deposits, EDR are concentrated in South Australia, the Northern Territory and Western Australia (Figure 2 and Figure 3). South Australia’s Olympic Dam is the world’s largest uranium deposit, with an EDR of 981 ktU (549,207 PJ).

Thorium

Thorium is a naturally occurring slightly radioactive metal that is three to five times more abundant in the Earth’s crust than uranium. It is less conducive to nuclear weapons proliferation and due to its greater energy-producing efficiency, generates substantially less radioactive waste. The most common source of thorium is monazite, a rare earth phosphate mineral that is a minor constituent of heavy mineral sand (HMS) deposits. On average, monazite contains approximately 6 per cent thorium and 60 per cent rare earth elements.

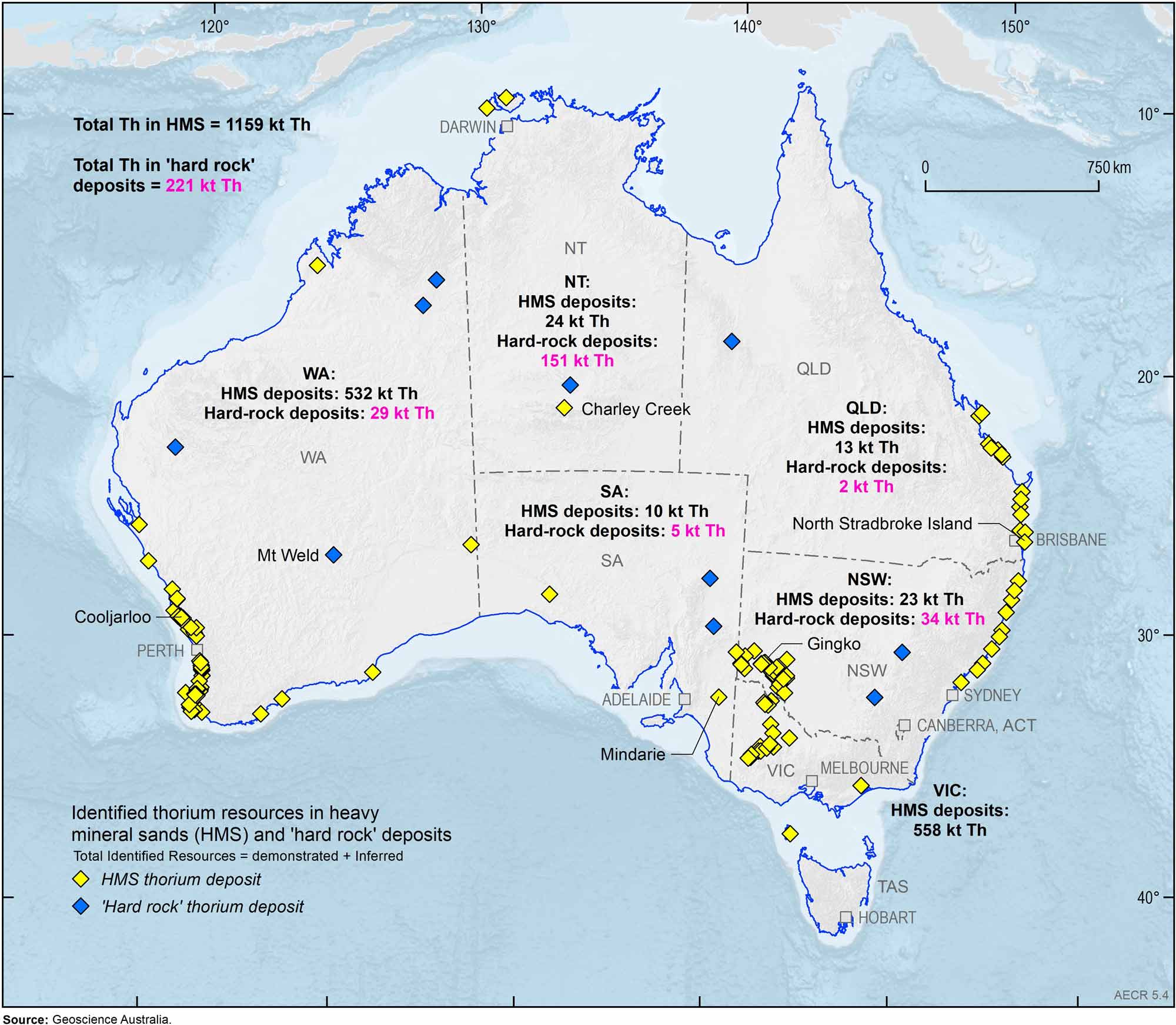

In Australia, approximately 80 per cent of thorium resources are contained in HMS deposits; the remaining 20 per cent are in rare earth element hard-rock deposits (Figure 4). Monazite and thorium resources are not generally published and so Geoscience Australia estimates the monazite (and hence thorium) content in deposits and classifies these estimated resources as Inferred Resources. Using this approach, Geoscience Australia estimates that Australia’s total identified in situ thorium resources were approximately 1,380 kt as of 31 December 2021.

Currently, no thorium is produced in Australia. Although HMS deposits containing monazite are currently being mined, the thorium is not recovered due to the lack of a thorium market.

Production

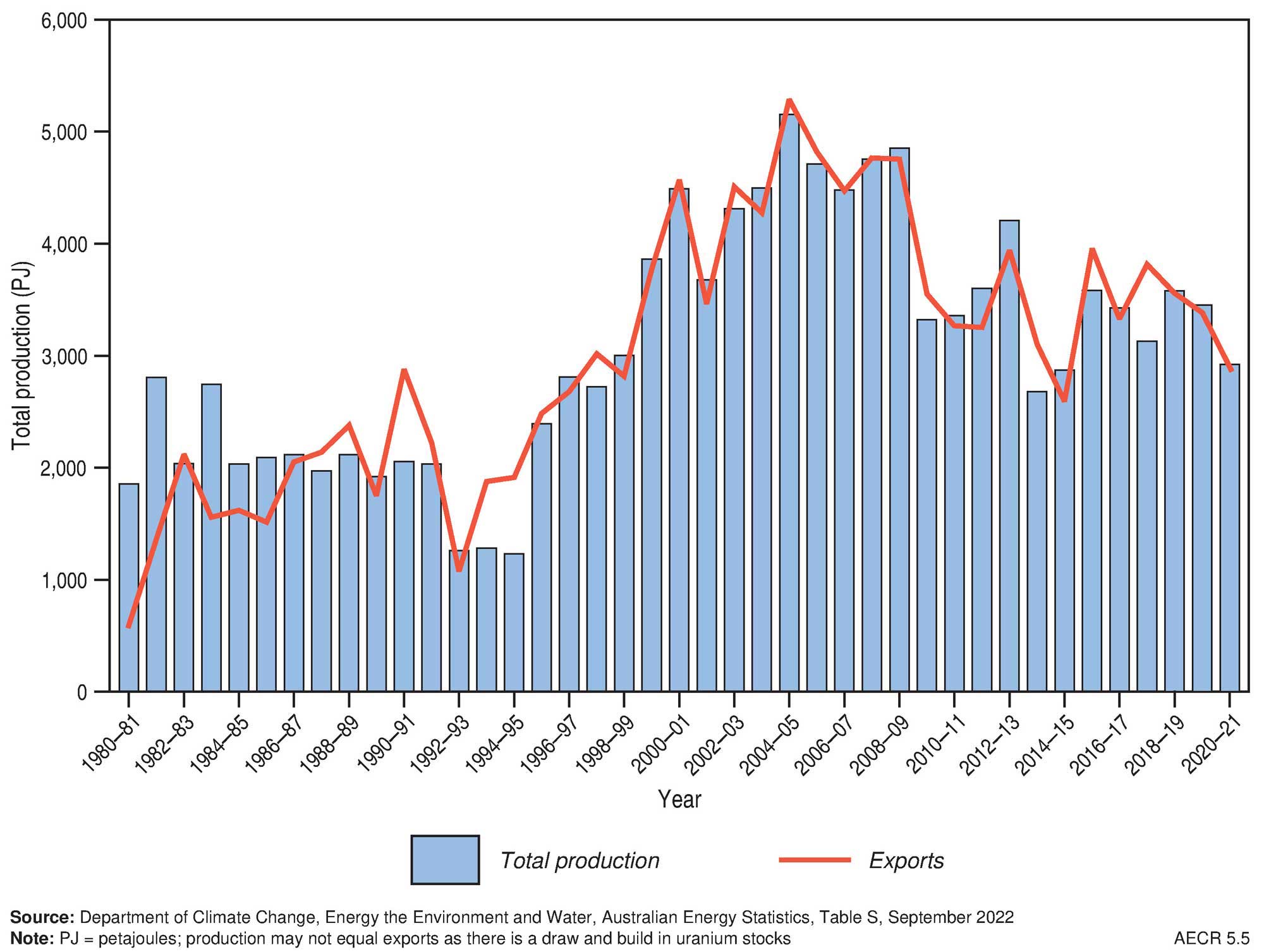

In 2021, Australia’s production of uranium was 3,798 tU (2,127 PJ; Figure 5), a drop of approximately 40 per cent compared with 2020. The fall in production was the result of the conclusion of operations at the Ranger mine as well as processing infrastructure upgrades at Olympic Dam. Nevertheless, in 2021 Australia and was the world’s 4th largest uranium producer (8 per cent) behind Kazakhstan (1st), Namibia (2nd) and Canada (3rd). This is in contrast to the previous 10 years where Australia’s uranium production has typically ranked 3rd behind Canada. In 2021, Australia’s uranium was produced from two operating mines: Olympic Dam and Four Mile, both in South Australia (Figure 6). Australia's uranium production will fall by approximately 20 per cent in the medium term due to the cessation of production at the Ranger mine in January 2021. All of Australia’s domestic production is exported.

The Honeymoon Mine in South Australia (Boss Energy), which has been in care and maintenance since 2013, has announced plans to re-start mining operations in Q4 2023. In Western Australia, the Cameco Australia’s Kintyre and Yeelirrie projects, Toro Energy’s Wiluna project, and Deep Yellow Limited’s, Mulga Rock project have all received environmental approval (Figure 6). Development of these projects is contingent on international uranium market conditions.

Global uranium production is dominated by a small number of countries, with Australia, Kazakhstan, Canada, Namibia, South Africa and Niger accounting for most production. Proterozoic unconformity-related deposits in Canada dominate the categories of lowest production cost. The sandstone-hosted resources of Kazakhstan, Niger and the United States comprise the next cost level. The Australian Olympic Dam breccia complex deposit is dominant in the key cost category of less than US$130/kgU.

Trade

Australia exports all its uranium production to countries which have signed bilateral safeguards agreement. There are a total of 44 countries with signed bilateral agreements. These agreements ensure that Australian uranium is only used for peaceful purposes and does not contribute to any military applications. Australian mining companies supply uranium under long-term contracts to electricity utilities in North America, Europe and Asia. In 2021, Australia exported 2,318 PJ (4,139 tU)—76 per cent of this was exported to Canada, while 11 per cent was sent to the European Union and 11 per cent to the United States.

World resources

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Atomic Energy Agency (OECD NEA and IAEA) describe 15 uranium deposit types. The largest tonnages are the sandstone, Proterozoic unconformity and Polymetallic iron-oxide breccia complex deposits (OECD-NEA and IAEA, 2020).

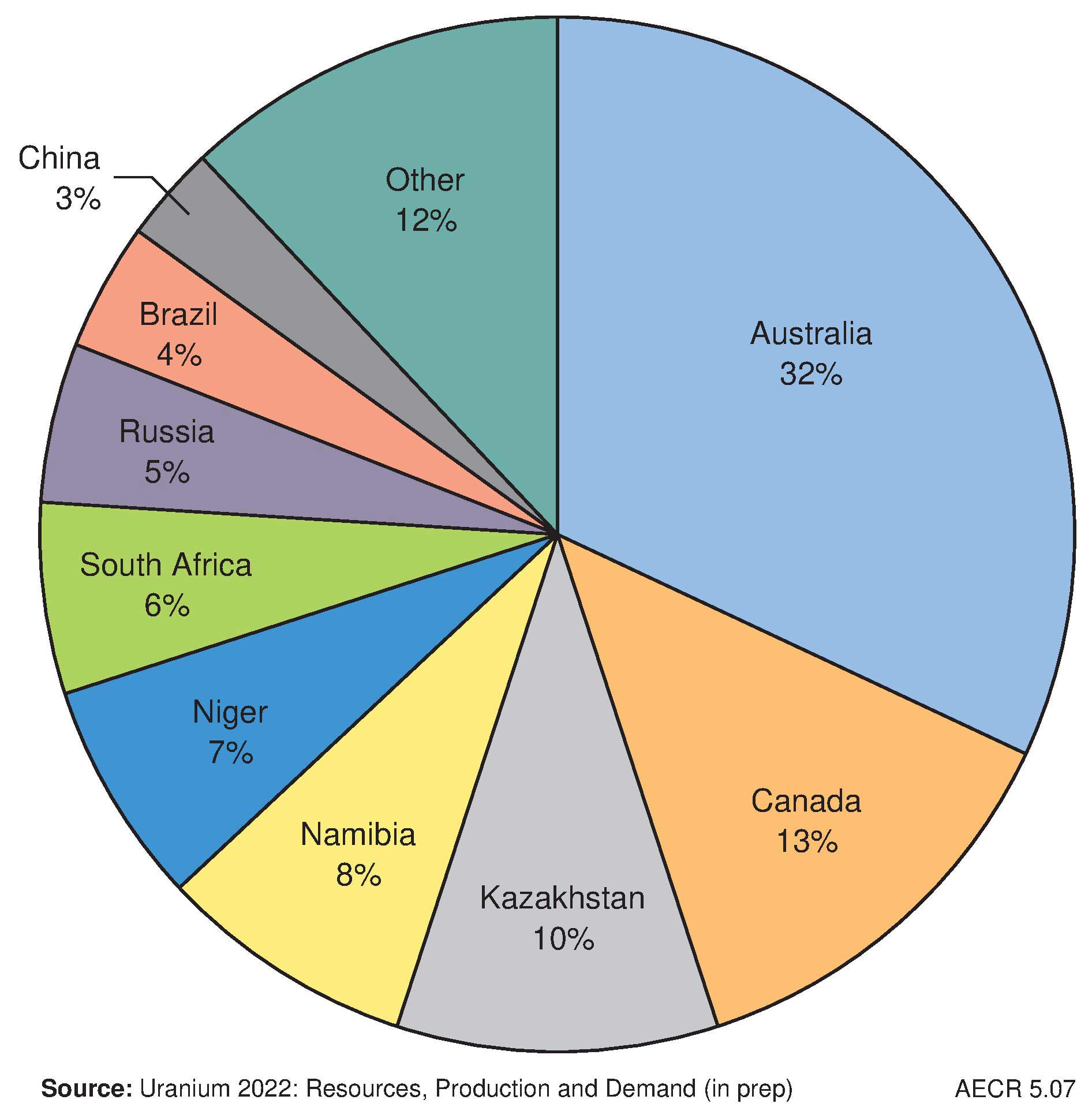

The recoverable volumes of World Reasonably Assured Resources (RAR) at less than US$130/kgU were estimated at approximately 3,815 million tonnes (Mt) in 2021 (OECD NEA and IAEA, 2022). Australia accounts for approximately 32 per cent of this global inventory (Figure 7; Table 1).

Extracting the latent energy value of thorium in a cost-effective manner is a challenge and requires considerable investment in research and development (World Nuclear Association, 2017). Another challenge is that thorium can only be used as a fuel in conjunction with a fissile material such as recycled plutonium.

Thorium-fuelled reactors have previously operated to generate electricity at Hamm-Uentrop in Germany (300 MWe, 1983–1989), at Peach Bottom (40 MWe, 1967–1974), Fort St Vrain (330 MWe, 1976–1989) and Shippingport (60 MWe, 1977–1982) in the United States (World Nuclear Association, 2017), with India having a longstanding program to develop thorium-based reactors. India has one small test facility in operation with a network of larger commercial facilities planned (World Nuclear Association, 2019; Power, 2019).

However, as international research into associated technologies tends to be small scale and intermittent (e.g. New Scientist, 2017), commercial use of thorium as a nuclear reactor fuel is still some decades away.

Table 1. Key uranium statistics

| Unit | Australia 2021 | World 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resources | |||

| Identified RAR recoverable at <US$130/kg U | PJ | 687,120 | 2,136,120 |

| t U | 1,227,000 | 3,814,500 | |

| Share of World | % | na | 100 |

| World Ranking | na | na | |

| Production | |||

| Annual production | PJ | 2,127 | 26,772 |

| t U | 3,798 | 47,808 | |

| Share of world | % | 8.0 | 100 |

| World ranking | no. | 4 | na |

| CAGR from 2011 | % | -3.3 | na |

| Exports | |||

| Annual exports | PJ | 2,318 | na |

| t U | 4,139 | na | |

| Export value | A$b | 0.46 | na |

Notes: t = tonne; PJ = petajoule; RAR = Reasonably Assured Resources; CAGR = compound annual growth rate; na = not available or not applicable. Data Sources: Resources data (2022 from OZMIN; World resources and production data (2020) from, Uranium 2022: Resources, Production and Demand (in prep); Export data from, Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Commonwealth of Australia Resources and Energy Quarterly March 2023, and have been converted from tonnes uranium oxide to tonnes uranium metal; Australia production world share and ranking sourced from the World Nuclear Association web site.

References

Australian Safeguards and Non-Proliferation Office (ASNO) 2022. Australian Safeguards and Non-Proliferation Office Annual Report 2021-2022 (last accessed 26 May 2023)

Department of Industry, Science and Resources 2023. Resources and Energy Quarterly, March 2023 (last accessed 24 May 2023).

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Australian Energy Statistics, Table S, September 2022 (last accessed 24 May 2023)

Hughes, A, Britt, A., Pheeney, J., Summerfield, D., Senior, A., Hitchman, A., Cross, A., Sexton, M., Colclough, H. and Hill, J. 2023. Australia's Identified Mineral Resources. Geoscience Australia, Canberra (last accessed 25 May 2023).

New Scientist 2017. Thorium could power the next generation of nuclear reactors (last accessed 26 May 2023).

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Nuclear Energy Agency and International Atomic Energy Agency (OECD NEA and IAEA) 2022. Uranium 2022: Resources, production and Demand (last accessed 26 May 2023).

Power 2019. Indian-designed nuclear reactor breaks record for continuous operation (last accessed 26 May 2023).

World Nuclear Association 2017. Thorium (last accessed 26 May 2023).

World Nuclear Association 2019. Nuclear Power in India (last accessed 26 May 2023).

World Nuclear Association 2023. World Uranium Mining Production for 2021 (last accessed 26 May 2023).

Data download

Australia's Energy Commodity Resources Data Tables - 2021 reporting period